Thus far human beings have essentially known two distinct and relatively stable modes of existence vis-à-vis their relationship to the land and the way in which they exploit it for food, shelter and other resources.

One mode, which is the more ancient, and includes ways of life such as hunter-gathering and pastoralism, is generally known as nomadism. Contrary to popular belief the nomadic community does not simply wander aimlessly over the earth but is stationed within a specific territory. The nomadic community's ability to exploit the land comes from its intimate knowledge of that specific territory, knowing which parts of it will be able to provide food in the summers and which in the winters. The nomad's year involves regular movements across that territory, determined by the rhythm of changing material circumstances that occur naturally through the cycle of the seasons.

The second way of life has no collective name as such, but involves continued settlement on one specific piece of land that is exploited for food, shelter and other resources all year round. Our current way of life, that of civilization, fits into this category as do all ways of life which derive food from permanent agriculture.

However, despite being relatively stable modes of existence there are certain extreme circumstances that can arise which can render them either ineffective or impracticable. Generally speaking those circumstances are either famine or war, but there are other circumstances, both natural and man-made that can produce the same effect. This effect, rendered most simply, is that the land can no longer provide the community with the resources or security that it needs for its continued existence. The only way for human beings faced with such circumstances to continue their existence is to migrate away from the homeland and go in search of new territories.

Human history has witnessed countless such migrations, and while individual humans can survive such catastrophes, communities and nations, groups of people with a shared identity, do not. The relationship between a community and the territory it inhabits is so fundamental to the construction of its identity that emigration from the land causes it irreparable damage, and within a number of generations the original identity ceases to exist and a new identity, albeit often bearing the traces of the previous, comes into being.

This transitional migratory phase, from leaving the homeland to settlement in the new country constitutes a third mode of human existence - wandering. Unlike the other two modes it is inherently unstable and despite its ubiquity within human experience it leaves either little or no trace within a nation's primary cultural artefacts. National mythologies, both ancient and contemporary, construct a people within a stable mode of existence, tied to a specific location. Since the telos of the wandering phase is the establishment of a new home and concurrently, a new identity, the traumatic experience of the wandering, where the very notion of a people's identity was in flux, generally does not become incorporated into the new mythology.

There is of course, one extremely famous exception to this rule – the national mythology of the Jewish nation. Instead of forgetting the wandering phase, the Jewish mythology enshrines it as the central and most formative experience.

The original ancestor of the Jewish people is known as Avraham Ha-Ivri – Abraham the one who crossed over, and during the first epoch of Jewish history the people were known exclusively as Ivrim (Hebrews), the landless, wandering element of their existence the factor that defined them. Even after the Ivrim transform and become the Bnei Yisrael (Israelites), their formative experience is not stable sovereignty in their own territory, but the cataclysmic emigration from Egypt and the resultant forty years of wandering in the Sinai Desert. And it is this episode which constitutes almost the entirety of the Torah (Pentateuch), the central and by far most important articulation of the Jewish national mythology. Just as telling is the slightly different version of Jewish history presented in the Haggadah, traditionally recounted on the first night of Passover, the festival most central to the construction of the national identity and the national myth, which states – Arami Oved Avi – my forefather was a wandering Aramean.

That the Jewish national identity was forged within traumatic, transitional periods of wandering may go a long way to explaining some of the unique difficulties in defining the essence of Jewish nationhood.

The primary goal of any way of life is to provide for the needs of human existence. No matter how these needs are defined, they always include the basic commodities of material existence, food, shelter and security, as well as the most fundamental elements of psycho-spiritual wellbeing, stability, purpose and a sense of place in the Universe. Both the nomadic and permanently settled ways of life utilise their relationship to the home territory to provide for the bulk of these needs.

The wandering mode of existence, however, cannot perform these functions. While the people may be able to carry some commodities with them at the beginning of the journey, these quickly run out. While they can bring memories of the homeland, these eventually fade. We can only speculate on the countless peoples who were forced off their original lands due to one catastrophe or another, who were utterly obliterated in a wandering phase, slowly starving to death through lack of stable resources, nursing the terminal depression of an incurable homesickness. Wandering is a mortally dangerous way of life, and is impossible to survive for a prolonged period.

However, the Torah claims that the Israelites wandered for a period of forty years, enough time for an entire generation to pass away, leaving alive not a single member who remembered the original land. By the time the Israelites' wandering comes to a close not a single one of them has ever known any way of life but that of wandering. A way of life that has no essential stability, no permanency what so ever. A way of life characterised by ceaseless movement, never to revisit old, familiar hunting grounds or watering holes, but always forging ahead to strange and alien places. No regular rhythms, no consistent cycles. No reliable food source to dispel the fears of hunger, no natural protection to defend against an enemy. A state of constant and perpetual existential crisis.

What effect would such an epoch have on the minds and imaginings of such a generation? How would such an experience, so unprecedented in the annals of history, affect their overall disposition? How would they relate to such basic concepts as home and away, friend and stranger, land and God?

The most ancient spiritual belief systems are based on a form of pantheism. The God-force is present within nature. It motivates the movement of the celestial bodies; it guides the flow of the river and the tides of the ocean. It infuses the tree and makes it reach for the heavens, it permeates the rock in its static grace. However, while the ancient pantheists recognised the God-force as the fundamental substance of existence, it was not present everywhere in equal amounts. Some sites were more sacred than others.

For most of the hunter-gatherers of antiquity, the land most infused with the God-force was their own. Coalescing into the form of the ancestral beings, within the borders of their homeland the Divine energy radiated sanctity and warmth, beyond those borders was the harsh and unforgiving outlands, home to demons, evil spirits and death.

As mankind transitioned from hunter-gathering to agriculturalism and nomadic pastoralism, new conceptions of divinity were conceived. The ancestral beings had become gods and goddesses and sacred places were now marked by a temple or shrine. Yet still sanctity resided only in ones own land, divinity only in one's own gods.

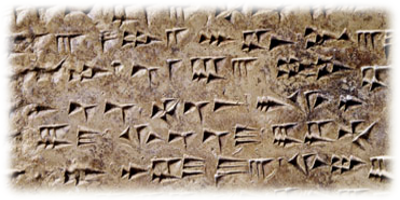

In the imagination of our ancient ancestors, man, god and land were interwoven in a perfect harmony. The ancestral beings of the Pitjantjatjara are bound to the particular topography of the Central Australian desert, the pantheon of Egypt is inextricably linked to that country's unique ecology and the civilization that grew up as a result of it. Furthermore, the ancestral beings of the Pitjantjatjara are honoured only by the Pitjantjatjara, not by the Taungurong or the Navajo or the Kamayurá. Horus, Osiris and Amen-Ra were worshipped exclusively by the Egyptians, not by the Babylonians, the Celts or the Maya.

But in what stream did the ancestral being of the Ivrim reside, in what grove rested the presence of the god of the Bnei Yisrael? When a people are forced off their land, they are also exiled from their gods. Without the physical link to the land the memory of the god will fade and die. And for a people who grew up with no land at all, not even its memory, to what god can they turn? Whom amongst the gods can they call their own?

The answer is one that we all know. Since they had no land of their own they could only turn to the God of all the lands. Since they were barely a people they had to turn to the God of all the peoples. For the wanderer only one god made sense. The One God of Everything.

The homeland and its gods are the source of all nourishment. The bond between human beings, the environment in which they live and the divine forces that both rule and animate that environment is one of ecological balance and reciprocity. The gods in their benevolence allow the land to yield its bounty and the people in thanksgiving keep the land in a state of health and render unto the gods that which is their due. Humans eat from the bounty of the land and the gods drink from the faith of humankind. It is a relationship of perfect symbiosis.

Acknowledging the divine role in the provision of sustenance would appear to be the cornerstone of the entire relationship between mankind and the divine. The ecology is the medium through which this sustenance is provided and is thus the bridge that links human beings to their gods. But the wanderer has no land; the ecology of the wilderness has no bounty to yield. The form of relationship that humans have enjoyed with their gods is not simply challenged by the wandering phase, it is shaken to its very foundations.

Almost immediately after their departure from Egypt, the Bnei Yisrael realised the impossibility of their new situation. Egypt may have had its problems, but in the god of the Nile provided food in abundance. Here, in the barren desert, was nothing. As they began to appreciate the doom inherent in their predicament the people cried out in anguish, a cry of bitter self-hatred and helpless impotence.

"If only we had died by the hand of YHVH in the land of Egypt, when we sat by the fleshpots, when we ate our fill of bread. For you have brought us out into this wilderness, to murder this whole congregation with starvation." (Exodus 16:3)

Hearing this cry, the Biblical God, in all of His righteous glory responds with a passion and a will that is not merely equal in its boldness to the people's despair, but by the sheer audacity of its improbability outstrips it entirely.

"Behold," thunders God, "I will rain bread down from the heavens!" (Exodus 16:4)

And sure enough God fulfilled his promise. That evening, continues the Book of Exodus, an immense flock of quail flew over the camp and as the Israelite's arrows sped to their targets, food began to literally drop from the skies. But God's promise did not end there. In the morning a dew covered the land around the encampment and as it evaporated in the scorching desert sun, a fine powder-like substance was left behind. At first the people were wary of this strange matter, for it was unlike anything they had ever known. But Moses appeared and reassured them, telling them that "This is the bread that YHVH has given you to eat."

The Israelites found that this powder could be worked in the same way as flour, and soon enough they were kneading it into dough and baking it into bread. According to Exodus, the Manna "was like coriander seed, white, and it tasted like wafers in honey." According to the Book of Numbers, "the taste of it was as the taste of a cake baked with oil." As time passed the mythology of the Manna became more fantastical. The Talmud (TB Yoma 75b) claims that that Manna was the food of the angels and that it was entirely absorbed by the body, without the need for excretion. The Midrash Tanchuma claims that it took on the taste of any food that you wished.

The Manna was undoubtedly the most important miracle of the wandering epoch. Whether one takes the myth at face value, or sees in it a metaphor for the continued nourishment of the people throughout their landless wandering, its miraculous dimension remains the same. For a people with no land, no stable pastures, no indigenous game and no means of permanent agriculture, to survive for a generational period of time is miraculous. The continual provision of one form of nourishment or another during the time of the wandering was the proof needed that this new God of the wanderers did not need an indigenous land to sustain His people. Even in the most barren and lifeless of places, this God could still provide.

None of the Manna's more fabulous qualities gave rise to any normative practice within the body of Jewish law. They remain purely in the realm of legend. However, the fact of the Manna itself provides the impetus for the Birkat Hamazon, the blessing made after one has eaten and is satisfied. The Talmud (TB Berachos 48b) tells us that the Birkat Hamazon in its original incarnation was instituted by Moses himself, as a thanksgiving for the miracle of the Manna.

In the twilight of the wilderness years, on the eve of the settlement in the new land, Moses gathered the people for one final address. The transition that this generation of wanderers is about to make is the most important change that will happen in their lives. Soon enough they will wander no more but become permanently settled in a new land. No longer will they need to rely on the grace of providence, but on the labour of agriculture.

It is within this context that the Covenant between Israel and the One God that lies at the core of the national myth comes into its sharpest focus. The people may have only learnt of the God of Everything through their wanderings, but He is now a part of their consciousness. And although the local deities of the new land will provide temptation, the memory of the One God can now never be erased.

Moses tells his people that just as in your time of greatest despair you turned to the One God for help, the One God's providence over you is now eternal. Just as the power of the One God nourished you and sustained you in the wilderness, it will be by the very same power that they will be nourished and sustained in the new land.

Moses' descriptions of the new land are saturated with promise. It is "a land of brooks of water, of fountains and depths, springing forth in valleys and hills." It is a land "flowing with milk and honey," a land of "wheat and barley and … olive oil." A land whose very "rocks are iron and whose hills are full of copper." And most importantly, it is a land whereby "the enterprise of agriculture will not cause poverty, where nothing is lacking in it."

The hope and expectation which permeates these descriptions points us towards the final element needed for survival through a wandering – the promise that it will one day be over. The landlessness of wandering can teach monotheism. In a barren desert a covenant can be forged. But despite the primacy of the wandering experience, the wilderness can never be home. So in his final address, where he recounts the trials of the wilderness and reiterates the dream of the Promised Land, Moses teaches his landless, homeless people one final lesson.

Home is not where you have come from; it is where you are going.

Like what you’re discovering? Continue the journey from Bible reader to translator.

|