"Lord of heaven and earth: the earth was not, you created it, the light of the day was not, you created it, the morning light you had not yet made exist."

The above quotation may sound like a passage from the Bible, but it is, in fact, a passage found in three literary texts inscribed on clay tablets that were discovered in the Royal Archives of the ancient city of Ebla.

A History of the Discovery of Ebla

Statue of Ibbit-Lim

In 1964 the Italian Archeological Mission, led by Paolo Matthiae, began a dig at Tel Mardikh in Syria. In 1968 the team uncovered a statue of Ibbit-Lim, King of Ebla, which included an Akkadian (Eastern Semitic language) inscription detailing Ibbit-Lim bringing an offering to the goddess Ishtar. Up until this time, the ancient city of Ebla was known from other Ancient Near Eastern texts, but its location was completely unknown. With the discovery of the statue, it was suspected that this may be the elusive Ebla. Then in the years 1974 through 1976 the Royal Library was discovered and these revealed that this was in fact the city of Ebla. The texts of the library, which dated to about 2500 BC, included about 2,000 complete tablets ranging in size from 1" to over a foot, 4,000 fragments and over 10,000 chips and small fragments, making this the largest library ever discovered from the 3rd Millennium BC.

The Archives of Ebla In-situ

The tablets were written with a cuneiform script, like Ugarit, but the language, as discovered by Giovanni Pettinato, the chief epigrapher for the Ebla excavation, was a Semitic language related to Canaanite, Phoenician, Ugarit and Hebrew, and came to be called Eblaite.

A Tablet from the Archives

It was revealed from the artifacts uncovered by the excavation of Ebla and through the study of the tablets that Ebla was a major economic power, a cultural center of the land of Canaan and a large metropolis of 260,000 people. The majority of the texts in the Royal Archive are related to the Economic and Administrative details of Ebla. However, the texts included historical information, religious texts, academic texts, agricultural details, laws, treatises and, of most interest to the study of Semitic languages, dictionaries (monolingual and bilingual) and encyclopedias, the oldest dictionaries and encyclopedias in history.

Up until the discovery of the Eblaite tablets the only Semitic language known to exist in 3rd Millennium BC was Akkadian. Now with this discovery, another Semitic language was found to be in use in the 3rd Millennium BC and has a very close relationship with the Hebrew language of the Bible.

Eblaite gods and the Bible

The gods of Ebla are for the most part the same gods worshiped by the Canaanites and other Semitic peoples of the area. The principal god of Ebla was Dagan and is referred to in the Eblaite texts as "Lord of Canaan," "Lord of the land" and "Lord of the gods." He is also mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible (see Judges 16:23) where it is spelled דגון (dagon, Strong's #1712). Other gods worshiped in Ebla, which can also be found in the Hebrew Bible, include Baal (בעל ba'al, see Numbers 22:41) and Ashtarte (עשתרות, see Deuteronomy 1:4).

And they have not cried unto me with their heart, but they howl upon their beds: they assemble themselves for grain and new wine; they rebel against me." (Hosea 7:14, ASV)

The Hebrew word for "grain" is דגן (dagan, Strong's #1715), which means "grain," but is also the name of the Canaanite god "Dagan," the god of grain. The Hebrew word for "wine" is תירוש (tirosh, Strong's #1715), which means "wine," but is also documented in the Eblaite tablets as the name of the Canaanite goddess "Tirosh," the goddess of wine. With this new understanding of these words, we can read the end of the above verse as, "they assemble themselves to Dagan and Tirosh; they rebel against me."

"Before him went the pestilence, and burning coals went forth at his feet." (Habakkuk 3:5, KJV)

The Hebrew word for "burning coals" is רשף (resheph, Strong's #7565), a noun meaning "flame," but is also the name of a Canaanite god, which is found in Ugarit and now Ebaite texts. The Hebrew word for "Pestilance" is דבר (daber, Strong's #1698) and it was not until it was discovered in the Eblaite texts that daber/dabir, was one of the gods of Ebla. Knowing that these two words are in fact the names of Canaanite gods, the text can be translated as, "Before him went Resheph, and Daber went forth at his feet."

El and Yah in the Ebla tablets

Many names in the Hebrew Bible include the words El and Yah within them. Examples of this are the names (אביאל (avi'el / Abiel, Strong's #22) meaning "My father is El," and (אביה (avi'yah / Abiah, Strong's #29) meaning "My father is Yah" and the names (מיכאל (mika'el / Michael, Strong's #4317) meaning "Who is like El," and (מיכיה (mika'yah / Michaiah, Strong's #4320) meaning "Who is like Yah."

The use of the Semitic words el (also il in some Semitic languages) and yah (also ya in some Semitic languages) in names is not unique to Hebrew, but are also found in the texts of Ebla. In the texts of Ebla are found the very same names mika'el and mika'ya. Another example from the texts of Ebla are the name eb-du-il (Servant of Il) and eb-du-ya (Servant of Ya), where eb-du is equivalent to the Hebrew word עבד (ebed, Strong's #5650). Another example from the Ebla tables is the names ish-ma-il (Il hears, the same as the name Ishamel) and ish-ma-ya (Ya hears).

Hebrew Names in the Ebla tablets

Many other names, some thought to have been late in origin, that are found in the Hebrew Bible are also found in the Archives of Ebla including;

| Hebrew | Eblaite | |

|---|---|---|

| Eber | Ebrium | |

| Abimelek | Abu-malik | |

| Canaan | Ka-na-na | |

| Adam | A-da-mu | |

| Yitro (Jethro) | Wa-ti-ru | |

| Yonah (Jonah) | Wa-na |

Similarities between Hebrew and Eblaite

The Eblaite language shares many similarities to the Hebrew language including a three-letter root system of words, the perfect and imperfect tense of verbs, the use of the yim suffix for double plurals and has a very limited use of adjectives. Eblaite uses many of the same letters as Hebrew for prefixes and suffixes to words. Like Hebrew, the letter vav (ו in Hebrew) is used as a prefix to words meaning "and," the letter yud (י in Hebrew) is used as a prefix to verbs meaning "he," the letter yud (י in Hebrew) is used as a suffix to words meaning "my, " the use of the letter kaph ( כ in Hebrew) is used as a prefix to words meaning "like" and the use of the letter kaph ( כ in Hebrew) is used as a suffix to words meaning "you." Besides these similarities between these two languages, the Eblaite language shares many words with the Hebrew language.

| Hebrew | Strong's | Eblaite | Translation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| katab | 3789 | katab | To write | |||

| natan | 5414 | natan | To give | |||

| yalad | 3205 | walad | To give birth | |||

| yada | 3045 | yada | To know | |||

| tob | 2898 | tub | Good | |||

| ebed | 5650 | eb'du | Servant | |||

| hhanan | 2603 | en-na | Show Favor | |||

| mal'kah | 4436 | Maliktum | Queen | |||

| ak'lah | 402 | akalu | Food | |||

| tehom | 8415 | ti-emu | depth | |||

| nephesh | 5315 | nupushtum | Soul | |||

| aniy | 589 | an-na | I | |||

| atah | 859 | anta | You | |||

| iyr | 5892 | ar | City | |||

| ab | 1 | ab | Father | |||

| yad | 3027 | iad | Hand | |||

| ayin | 5869 | in | Eye |

Defining Hebrew words through the Ebla Tablets

and he made him to ride in the second chariot which he had; and they cried before him, Bow the knee: and he set him over all the land of Egypt. (ASV)

The Hebrew word translated as "bow the knee" is אברך (ab'rek), a word of uncertain meaning and is thought to be an Egyptian word. However, if this is a Semitic word, it is clear that it is derived from, and related in meaning to, the root ברך (barak, Strong's #1288), meaning "to bend the knee." In the Eblaite dictionaries of the archives is the Eblaite word a-ba-ra-gu-um meaning "superintendent." As the Eblaite letter "g" is often the equivalent of the Hebrew letter "k," we can read this word as a-ba-ra-ku-um, the Hebrew word ab-rek. The translation of "superintendent" for this Hebrew worddoes in fact relate to the root barak in the sense of bowing the knee before one in authority, the "superintendent." It also fits with the context of the passage as the Pharaoh set him over all the land.

then shall they give every man a ransom for his soul unto the LORD (Exodus 30:12, KJV)

My beloved is unto me as a cluster of camphire in the vineyards of Engedi. (Song of Solomon 1:14, KJV)

In the two passages above is the Hebrew word כפר (kopher, Strong's 3724), where it is translated as "ransom" in the first verse and "camphire" (also known as "henna") in the second. The meaning of this word has been deduced from the Aramaic and Syriac languages, but can now be defined from Eblaite where Kopher is the Eblaite word for "copper." This fits in with the context of our two passages where a "ransom" is paid with "copper" and "camphire/henna" is a copper-colored dye.

Three pounds of gold (1 Kings 10:17, ASV)

The Hebrew word for "pound" מנה (maneh, Strong's #4488) is thought to be the Aramaic word minah, a Babylonian unit of measurement from the 1st Millennium BC. However, the Eblaite dictionaries reveal that this word is of Canaanite origin from at least the 3rd Millennium BC and is actually the origin of the Aramaic word minah.

God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble. (Psalm 46:1, ASV)

The structure of this verse implies a chiastic structure where the first part of the verse is paralleled with the second part. This means that the first word of the verse, אלהים, (Elohiym, Strong's #430), which is translated as "God," is a parallel with the last word מאד (me'od, Strong's #3966), which is translated as the adverb "very," but does not work as a parallelism. It was discovered that the Eblaite word ma'ad, the same spelling as the Hebrew word me'od, was often used as a noun meaning "the Grand One." By translating the Hebrew word me'od as "the Grand One," the parallel appears.

Of particular interest is the Eblaite word nabiu, which the texts refer to as holy men who travel from region to region announcing the divine message, in other words-prophets. This word is derived from the Eblaite verb naba. The Hebrew word for a prophet is נביא (nabi', Strong's #5030), which is derived from the Hebrew verb נבא (naba, Strong's #5012). Because this verb is only used in the context of prophesying in the Hebrew Bible, its literal meaning was uncertain, but thought to mean "to announce," the meaning of this verb in the later Arabic language. But now, thanks to the dictionaries found in Ebla, it has been confirmed that the verb נבא (naba) did in fact mean "to announce" in ancient times.

The common Hebrew word for a child is ילד (yeled, Strong's #3206), but the Hebrew word ולד (walad, Strong's #2056) appears once in the Hebrew Bible (Genesis 11:30) instead of ילד (yeled) for "child," and it has been proposed that the word ולד (walad) was a defective spelling and should instead be read as ילד (yeled). However, the Eblaite text reveals that the Semitic word ולד (walad) was the original spelling and Genesis 11:30 preserves a more ancient spelling of the word.

In the Hebrew language is the word בכור (bekor, Strong's #) meaning "firstborn." In the Eblaite language the word for "firstborn" is bukalu, almost identical to the Hebrew equivalent, except that it is spelled with the letter "L" rather than with an "R." This shift of letters between different languages is a common occurrence and can also be seen in the Hebrew language itself. For instance, a frequent Hebrew word for a "word" is אמר (emer, Strong's #561) and would appear to be derived from the root אמר (A.M.R). However, the root אמר means "to be weak," but another frequent Hebrew word for a "word" is מלה (milah, Strong's #4405) and is spelled with an "L" instead of an "R," which indicates that the Hebrew word אמר (emer) may have originally been spelled אמל (emel). Other letter shifts found between Hebrew and Eblaite, which can also be found in the Hebrew language itself, are "K" and "Hh," and "B" for "G" and "G" for "K."

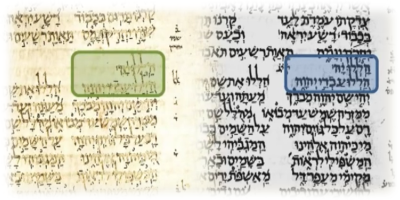

Eblaite and the Book of Job

The Eblaite language has shed much light on the Hebrew language of the Bible. For instance, the Hebrew word for water is מים (mayim, Strong's #4325), but written as מי (mey) in the possessive form (water of...). In Job 9:30 is the phrase "'water of' snow," but instead of the word מי (mey), the word מו (mw) is written. The Masorites assumed that this was a defective spelling and in the margins of the Masoretic text (1000-year-old Hebrew Bible) wrote מי as the correction. The Masorites may have been a bit premature in their corrections to the text as in the Eblaite language, as discovered in the tablets, the word for water is mw, and Job is preserving the more ancient Semitic spelling for water.

The Eblaite language has also revealed the meaning of many Biblical words that were up until now uncertain or unknown. An example is the word מנלם (min'lam, Strong's #4512), which is translated as "possessions" in the passage below.

He shall not be rich, neither shall his substance continue, Neither shall their possessions be extended on the earth. (Job 15:29, ASV)

Because the word min'lam only appears once in the Hebrew Bible, here in this verse, and was not found in any other Semitic language, the meaning of this word was unknown. The only clue to its meaning could be derived from its parallel with words "rich" and "substance" in this verse and therefore had some meaning of "wealth." In the Eblaite language was found the word ma-ni-lum, which meant "cow," but can also mean "property."

Mitchel Dahood, S.J. wrote in The Archives of Ebla: Ebla, Ugarit and the Bible, "How did this hapax legomenon [a word of single occurrence] get into Job, a book dating to perhaps the eighth or seventh century B.C.? A chronological chasm of some eighteen centuries separates Ebla from Job."

Most scholars date the Book of Job to between the 7th and 4th centuries B.C., but in my own research into the language of the book of Job I have concluded that the book of Job is much more ancient, probably the 3rd millennium B.C. The above studies of the words mw and min'lam in the book Job are additional evidences to support my hypothesis.

Eblaite, Ugarit and Hebrew

When the Ugaritic texts of Ras Shamra were discovered almost 100 years ago, Scholars cautioned using them to assist with Biblical interpretation as is pointed out in The Archives of Ebla: An Empire Inscribed in Clay.

Since the discoveries at Ras Shamra beginning in 1929, many biblical scholars have shown a certain reluctance to exploit this new textual material because they felt that it was too early (circa 1375-1190) and too far away to be relevant for solving problems in texts composed in Hebrew and in Palestine in the first millennium B.C. In his review of L. Sabottka, Zephaniah, a work which attempts to apply Ugaritic data to the text of the prophet which bristles with difficulties, F. C. Fensham writes, "One must, however, be very cautious in comparing Ugaritic material from the fourteenth to twelfth centuries B.C with the Hebrew of Zephaniah (ca. 612 B.C.), with the interval of about six hundred years in which the meaning of a word or a literary device could have changed enormously. In cases where one has no choice but to compare Ugaritic and Hebrew so far apart, it would be wise to put a question mark after one's solution." But Ugaritic and Hebrew no longer seem to be so far apart, thanks to the Ebla tablets of 2500 B.C. which illumine the Hebrew text on point after point and which in turn are elucidated by the biblical record. Scholars are, in fact, beginning to remark facetiously that the Ugaritic texts may be much too recent to be relevant for biblical research! Not the least of Ebla's contributions will be the gradual demolition of the psychological wall that has kept the Ras Shamra discoveries out of biblical discussions in some centers of study and from committees convened to translate the Hebrew Bible into modern tongues.

Like what you’re discovering? Continue the journey from Bible reader to translator.

|