מַה שְּׁמוֹ וּמַה שֶּׁם בְּנוֹ

כִּי תֵדָֽע

What

is his Name,

and what

is his Son's Name,

if thou

canst tell?

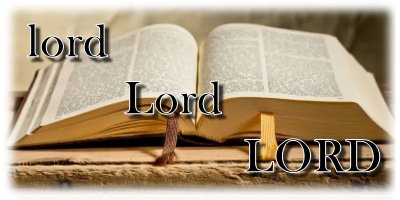

1. In the Hebrew Scriptures

“ יהוה ” represents the personal name of the Creator, the Elohim of

Israel. It is found there over 6,600 times.1 Often called the “Tetragram” or “Tetragrammaton”

(meaning roughly, "The Four Letters") by technical writers and lecturers,

this word, יהוה , is composed of the four letters

Yud י , Hei ה , Vav ו , and Hei ה . Do we know what it means or how to pronounce it? In most

Jewish and Christian circles it is not spoken. Jews call him in Hebrew, Adonai אֲדֹנָי (Lord),

or HaShem הַשֵּׁם (The Name), while

Christians use, “The LORD.”2 These

are titles. They are substitutions for his Name. But, why? Why is his Name

not used when speaking to him or about him? To answer this question we must

go to the Mishnah, which was compiled at the beginning of the third century.

Our answer lies there, in the so-called “Oral Torah” or “Oral Law”

which embodies Pharisaic/Rabbinic tradition from second Temple times.

Sanhedrin 10:1 All Israel have a portion in the world to come... BUT these are those

who have no portion in the world to come:

one who says that resurrection is not found in the Torah, one who says the

Torah is not from heaven, and an epicurean. R. Akiva says: one who reads the

uncanonical books and one who whispers [a charm] over a wound and says, (Exodus

15) “I will bring none of these diseases upon you which I brought upon the

Egyptians, for I am HaShem who heals you.” Abba Shaul says: Also one who Pronounces the Name according to its letters.3

2. This speaks for itself,

does it not? Among those who have no portion in the world to come, according

to the Rabbis, is he who pronounces the Name as it is written. It appears

that the Name was only allowed to be spoken by the priests in the temple courts

when they were blessing the people.

Sotah

7:6 How is the Priestly Blessing done? In

the province they say it as three blessings, but in the temple as one blessing.

In the temple

he says the Name as it is written,4 but in the province, its pseudonym.

3. According to the Mishnah, when the “Priestly Blessing”

of Numbers 6:24-26 was recited over the people in the temple, the Name was

spoken as it was written. When the blessing was said outside the confines

of the temple courts, the “Pseudonym” was used. It is generally understood

that “Adonai” is the pseudonym to which reference is made but we know

that HaShem הַשֵּׁם (The Name) was

also used.5

4. Why is the Name not spoken in Jewish and Christian

circles? Because the Rabbis have forbidden it. In so doing they violate the

Torah and disregard the will of the One who wants his Name mentioned in every

generation.

Exodus

3:14-15 ... יהוה ...This is my Name forever,

and this is my Mention (“memorial” KJV) to all generations.

5. The Creator expressly states here that יהוה is his Name

forever. It is how he wants to be remembered or “mentioned” to all generations.

While “memorial” (as the King James Version renders the Hebrew zeikher זֵכֶר ) might be appropriate

for one who is dead, it is not fitting for him who is The Living One. The

word zeikher זֵכֶר , from the root Zayin Kaf

Reish ז.כ.ר.

, conveys the thought that this is how he wants

his people to “call him to mind” or “mention” him.6 One specific way to mention him is to take our oaths

in his name. This is expected of us.

Deuteronomy

10:20 You shall fear יהוה your Elohim;

him shall you serve, and to him shall you cleave, and in his Name shall you

swear.

6. This instruction is for both houses of Israel as well

as the Gentile. It is valid for the native-born Hebrew and grafted-in Goy.

It is in force for all who would learn his ways and be his people.

Jeremiah

12:16-17 “And it shall come to pass, if

they will diligently learn the ways of my people, to swear by my Name, ‘

יהוה lives,’

as they taught my people to swear by Ba’al, then shall they be built in

the midst of my people. But if they will not listen, I will totally uproot

and destroy that nation,” says יהוה

.

7. So, how can we obey the Torah by mentioning his Name

and using his Name in our oaths if we are obeying the Rabbis who tell us not

to do so? It is obvious we can’t do both. We have to make a choice. Where

will our allegiance be? Will it be to the Torah or to the Rabbis? Should we

continue listening to those who set aside the commandments of the Almighty?

What does Isaiah say? What does Yeshua say?

Isaiah

8:20 To the Torah and to the testimony!

If they will not speak according to this word, they have no light.

Isaiah

29:13 Adonai has said, “Because this people

draw near with their mouth, and with their lips they honor me, but they have

removed their heart far from me, so that their fear toward me is the erudite commandment of men...”7

Shem

Tov's Hebrew Matthew 15:1-9 Then the sages

and the Pharisees came to Yeshua and said to him, “Why do your disciples

transgress the reforms of antiquity in that they do not wash their hands before

eating?” But Yeshua said to them, “And why do you transgress the words

of Elohim for the sake of your reforms?... You despise the words of Elohim by your reforms... Woe, hypocrites!

Behold Yeshayah prophesied of you, saying, ‘Thus says יהוה : Because this

people draw near with their mouth, and with their lips they honor me, but

they have removed their heart far from me, so that their fear toward me is

the erudite commandment of men...’”8

Shem

Tov’s Hebrew Matthew 23:2-3 The Pharisees

and sages sit in the seat of Moshe. So now, keep doing everything he tells

you, but do not do according to their reforms and precedents, for they talk and do not act.9

8. The practice of not saying the Name is one of the “reforms”

of the Rabbis. It is at variance with the Torah, it is at variance with the

Prophets and it is at variance with Messiah. This practice has, like Baal

worship, caused the people of Elohim and the world at large to forget his

Name.10 We cannot take back the lost ground, however, without

a systematic and objective approach to the whole subject and the will to make

a difference in our own spheres of influence. In order to approach it thus,

we’re going to have to examine and embrace the linguistic evidence we find

in the pages of the Tanakh, the Hebrew Scriptures.11

9. As you probably are already aware, the majority of

the Tanakh was written in the Hebrew language. It would seem logical, therefore,

to assume that the Creator’s Name, first encountered in a Hebrew context,

written to a Hebrew speaking audience, would be a Hebrew name. Many, surprisingly,

believe that the Name is “heavenly” in nature and therefore not a Hebrew

name at all. Such unverifiable subjectivity must be completely abandoned if

we are ever to get to the heart of the matter. The facts indicate that the

Creator’s Name is a Hebrew name. I am of the opinion that we shall discover

within the structure of the Hebrew language itself the form of this Name or

we shall not discover it at all.

Eh’yeh

אֶהְיֶה

10. Let’s start with the basics. When the Almighty first

revealed his Name to Moshe in Exodus 3:14 he explained it as signifying, "I

Am." This is extremely important as the meaning of the Name, “

יהוה ,”

will eventually lead us to its true pronunciation. Meaning and pronunciation

are inseparable.

Exodus

3:14-15 And Elohim said to Moshe, “I Am

That I Am.” And he said, “Thus shall you say to the sons of Yisra’el:

I AM has sent me to you.” And Elohim said moreover to Moses, “Thus shall

you say to the sons of Yisra’el: יהוה

the Elohim of your fathers, the Elohim of Avraham,

the Elohim of Yitzchak, and the Elohim of Ya’akov, has sent me to you. This

is my Name forever, and this is my Mention to all generations.

11. “I Am That I Am”

translates the phrase eh’yeh asher eh’yeh אֶהְיֶה אֲשֶׁר אֶהְיֶה . Eh’yeh אֶהְיֶה is

a verb of the Pa’al, or Kal, conjugation. We’ll discuss the seven conjugations

in more detail later. For now it is enough to know that this conjugation is

the simplest and conveys action in its simplest or most basic form.12 The root of this verb is Hei Yud Hei ה.י.ה. (

הָיָה ) and

has a basic meaning of, “to be, to exist.”13 The

Aleph א

at the beginning

of the three letter root signifies the imperfect or future tense, first person

singular - “I will...” The meaning of the root Hei Yud Hei ה.י.ה. (to be) taken

together with the Aleph א modifier at the beginning

(I will) signifies, “I will be,” or, “I am.”

12. Immediately after saying, “Eh’yeh אֶהְיֶה has sent me to you,” the Creator says, “

יהוה ... has

sent me to you.” This would seem to indicate that יהוה , like eh’yeh אֶהְיֶה

, is a verb. We should expect it to also be of

the Kal conjugation. The root of this verb is Hei Vav Hei ה.ו.ה. 14 and

has a basic meaning of, “to BREATH... hence, to live... and in the use of the language, to be, i.q. the common

word הָיָה .”15 The Yud י at the beginning of the three letter root signifies

the imperfect or future tense, third person singular - “He will...” The

meaning of the root Hei Vav Hei ה.ו.ה.

(to be) taken together with the Yud י modifier at the beginning (He will) signifies, “He

will be,” or, “He is.” Our search, then, is for how to say, “He will

be,” using the root Hei Vav Hei ה.ו.ה. .

13. What can we learn of how he wants to be mentioned from

Exodus 3:14? On the surface, it would appear, very little. But in actuality

we have already learned a great deal. By way of inference we have learned

that the Name is a verb of the Kal conjugation. And by knowing the tradition

of “no mention” we can learn how the Name is not said. How? Simply by

looking at the vowels the scribes put within it. In Exodus 3:14 and wherever

else יהוה stands by itself in the Hebrew text it appears as Y’hvah יְהוָה or Y’hovah יְהֹוָה

, depending on the edition of the Tanakh. We get

“Jehovah” from this. Whenever יהוה

is found with Adonai אֲדֹנָי (Lord) as in

אֲדֹנָי יהוה it appears as Y’hvih יְהוִה

or Yehovih יְהֹוִה . Why?

Well, it has to do with the nature of the Hebrew language, how it fell into

disuse, and, of course, Rabbinic tradition.

The

Hebrew Language

14. Hebrew is, and always

has been, a language of consonants. A few of those consonants, were sometimes

also used to represent vowel sounds. They are four: Aleph א , Hei ה , Vav ו , and Yud י . Not surprisingly,

they are known as “vowel-letters.”16 The

Aleph א

and Hei ה can represent an “ah”

sound like the “a” in “father.” The Vav ו can be an “oh” like the “o” in “no” or an “oo”

like the “u” in “flute.” The Yud

י can

represent "ee” like the “i” in “machine” or “ay” like the “ei”

in “eight.”

15. Different words are often written with exactly the

same consonants. For instance, in print, the letters דבר can be understood

as, "he spoke," "it was spoken," "word," "word of," "plague," or "pasture."17 The pronunciation and meaning depend on the context

and the place of the word in the sentence. This poses little difficulty to

native speakers of the language. Context and syntax are usually enough to

decide which word a certain combination of letters represents, even when the

word contains no vowel-letters. Even if multiple pronunciations are possible

for any particular combination, it's not too difficult to know how it should

be pronounced. Many more examples could be cited, but it would not benefit

us here. Just thumb through the Analytical Lexicon sometime and you'll see

how many combinations are possible for certain words.

16. Many assert that Aramaic replaced Hebrew as the common

dialect of Jewish life sometime during the Babylonian captivity. John Parkhurst,

in his Lexicon of New Testament Greek, gives seven reasons why this is not

so. I will quote him briefly.

1st.

Prejudice apart, Is it probable that any people should lose their native language

in a captivity of no longer than seventy years?...

2dly.

It appears from Scripture, that under the captivity the Jews actually retained not only their language,

but their manner of writing it, or the form and fashion of their letters.

Else, what meaneth Esth. viii. 9, where we read that the decree of Ahasuerus, or Artaxerxes Longimanus, was written

unto every province according to the writing thereof, and unto every people

after their language, and to the Jews according

to their writing, and according to their language?...

3dly.

Ezekiel,

who prophesied during the captivity to the Jews in Chaldea, wrote and published

his prophecies in Hebrew...

4thly.

The prophets who flourished soon after the return of the Jews to their own

country, namely Haggai and Zechariah, prophesied to them in Hebrew, and so did Malachi, who seems

to have delivered his prophecy about an hundred years after that event...

5thly.

Nehemiah,

who was governor of the Jews about a hundred

years after their return from Babylon, not

only wrote his book in Hebrew, but in ch. xiii, 23, 24, complains that some of the

Jews, during his absence, had married wives of Ashdod, of Ammon, and of Moab, and that their

children could not speak יהודית

the Jews’ language, but spake a mixed tongue... But how impertinent is

the remark, and how foolish the complaint of Nehemiah, that the children of some Jews, who had

taken foreigners for wives, could not speak pure Hebrew, if that tongue had ceased

to be vernacular among the people in general a hundred years before that period?...

6thly.

It is highly absurd and unreasonable to suppose that the writers of the New

Testament used the term Hebrew to signify a different language from that which the

Grecizing Jews denoted by that name; but the language which those Jews

called Hebrew after the Babylonish captivity, was not Syriac, or Chaldee, but the same

in which the law and the prophets were written...

Lastly.

It may be worth adding, that Josephus, who frequently uses the expressions

thn ‘EBRAIWN dialekton [the Hebrew dialect], glwttan thn ‘EBRAIWN [the Hebrew

tongue],

‘EBRAISTI [in Hebrew]18, for the language in which Moses wrote... tells us... that towards the conclusion of the siege

of Jerusalem he addressed not only John, the commander of the Zealots, but

toij polloij the (Jewish) multitude who were with him, ‘¸EBRAIZWN in the Hebrew tongue, which was therefore the common language of the Jews

at that time, i.e. about forty years after our Savior’s death.

On the

whole, I conclude that the Jews did not exchange the Hebrew for the Chaldee language at

the captivity...19

17. The text of the Mishnah,20 compiled at

the beginning of the third century C.E. by Judah the Prince, corroborates

this point of view. Written almost entirely in Hebrew,21 it reflects not only the “Oral Tradition” of second

temple times, but the language in which that tradition was communicated. In

the words of the Mishnah, “A man is obligated to speak in his Rabbi’s

tongue” (Eduyot 1:3). M. H. Segal, in discussing the Hebrew of the Mishnah,

has this to say on the subject:

In conclusion,

we must refer briefly to the linguistic trustworthiness of the Mishnaic tradition...

Its trustworthiness is established by the old rule, older than the age of

Hillel, that a tradition - which of course, was handed down by word of mouth

- must be repeated in the exact words of the master from whom it had been

learnt: חַיָּב אָדָם לוֹמַר

בִּלְשׁוֹן רַבּוֹ [A man

is obligated to speak in his Rabbi’s tongue]22. This rule was strictly observed throughout the Mishnaic

and Talmudic periods (cf. ‘Ed. i.3, with the commentaries; Ber. 47a; Bek.

5a), and was in fact, the basis of the authority of the Oral Law. So careful

were the Rabbis in the observance of this rule that they often reproduced

even the mannerisms and the personal peculiarities of the Masters from whom

they had received a particular tradition, or halaka. This rule makes it certain

that, at least in most cases, the sayings of the Rabbis have been handed down

in the language in which they had originally been expressed.23

18. The decline of Hebrew as a spoken language is thought

to have begun with the fall of the Hasmonean dynasty and the rise of Herod

to power in 63 B.C.E. A number of circumstances contributed to its final demise.

Mr. Segal sums it up well.

The

destruction of many of the native families in the bloody wars which accompanied

the coming of the Romans and the establishment of the Herodians (whose original

language was probably Aram.); the closer connexion between Jerusalem and the

Aram. Jewries of Syria and the Eastern Diaspora which followed on the incorporation

of Palestine in the Roman Empire; and the settlement of those Aram.-speaking

Jews in Jerusalem, all tended to spread the use of Aram. at the expense of

MH. But MH still remained a popular speech, as is testified by numerous passages

in its literature... Finally, the destruction of Jewish life in Judea after

the defeat of Bar Kokba (135 C.E.), and the establishment of the new Jewish

centre in the Aram.-speaking Galilee, seem to have led to the disappearance

of MH as a popular tongue.24

19. It appears that Hebrew remained a spoken tongue well

into the fourth century.25 As

such, its mode of written communication (letters and vowel-letters) was more

than adequate to facilitate understanding. As it fell into disuse by the masses,

however, it became more and more difficult to decipher written texts. This

problem became most acute in relation to the Tanakh. As use of the language

diminished, the proper reading of the sacred scrolls increasingly came into

question. How could the accepted reading of the text be maintained and perpetuated

as the language slowly died? This was the challenge. Sometime in the sixth

or seventh century C.E. a group of scribes rose to the occasion. They invented

a set of vowel signs or "points" to accompany the consonants and preserve

the "traditional" reading of the Hebrew Scriptures.26 They were placed within, above and below the letters of

the text.27

Y’hvah

יְהוָה and Y’hovah יְהֹוָה

20. Since Pharisaic “reform” dictated an outright ban

on speaking the Name “according to the letters,” whenever the scribes

encountered “ יהוה ” they inserted into it, with a slight modification, the

vowels of the word Adonai אֲדֹנָי

(Lord). This was to signify to those who would

read the text that Adonai אֲדֹנָי

was to be read instead. Depending on the edition of the Tanakh, this

looks like Y’hvah יְהוָה or Y’hovah יְהֹוָה

. Now, the discerning student is going to notice

right away that neither set of these vowels matches exactly the vowels under

Adonai אֲדֹנָי

. Bear with me

for just a few lines. I’ll try to make the reason as simple as possible.

21. The first difference is in the vowels under the initial

letter. Under the Yud י of Y’hvah יְהוָה and Y’hovah יְהֹוָה

is a Sh’va ( ְ ). Under the Aleph א of Adonai אֲדֹנָי is a Hataph Patach

( ֲ ). The difference in vowels is due to the difference

in the nature of the two letters. The Yud י , being a standard consonant, can take a Sh’va at the beginning

of a word. The Aleph א , being in essence a mild guttural, cannot. It must take

a compound Sh’va, (in this case a Hataph Patach) at the beginning of a word. The scribes simply transferred

the nature of the short vowel under the Aleph א to the vowel under the Yud י rather than the

exact vowel.

22. The second vowel in Adonai אֲדֹנָי is a Holam ( ֹ ). In the case

of Y’hvah יְהוָה it is missing.

This is, I believe, to make doubly sure Adonai אֲדֹנָי

would be read, as Y’hvah יְהוָה is quite

redundant and impossible to pronounce.

Y’hvih יְהוִה

and Y’hovih יְהֹוִה

23. Often times the words Adonai אֲדֹנָי and יהוה appear side

by side in the Hebrew text. When the scribes encountered this combination

they inserted the vowels for the word Elohim אֱלֹהִים

(Elohim) into the Tetragram so that Adonai Elohim would

be read instead of Adonai being read twice. Depending on the edition of the Tanakh, this

looks like Adonai Y’hvih יְהוִה

אֲדֹנָי

or Adonai Y’hovih

אֲדֹנָי יְהֹוִה . Again, there is a

discrepancy between the vowels under the Yud י of יהוה

and the Aleph א of Adonai

אֲדֹנָי for the same reasons as stated above. The pronunciation Y’hvih יְהוִה is every

bit as impossible as Y’hvah יְהוָה .

24. It is worth noting that the edition of the Tanakh which

uses Y’hvah יְהוָה also uses Y’hvih יְהוִה

. The other edition uses Y’hovah יְהֹוָה and Y’hovih יְהֹוִה

.

25. All this has been said to help us see that the vowels

under יהוה are not its real vowels. The following entry is from the popular four volume

Even-Shoshan dictionary used in Israel. It verifies what has just been asserted.

יְהֹוָה,

יֱהֹוִה... נִבְטָא "אֲדֹנָי"

אוֹ "הַשֵּׁם" אוֹ "אֲדשֶׁם" - אִם נִקּוּדוֹ

"יְהֹוָה"; אוֹ "אֱלֹהִים, אֱלֹקִים" - אִם נִקּוּדוֹ

"יֱהֹוִה", מִשּׁוּם הָאִסּוּר לַהֲגוֹת אֶת

הַשֵּׁם בְּאוֹתִיּוֹתָיו:

יְהֹוָה,

יֱהֹוִה ... pronounced “Adonai”

or “HaShem” or “Adoshem” - when its vowels are “ יְהֹוָה ”;

or “Elohim, Elokim” - when its vowels are “ יֱהֹוִה ”, because of

the prohibition of uttering the Name according to its letters.28

26. By the looks of the vowel points under the Tetragram

in this entry, it appears that there must be at least a third edition of the

Tanakh. The vowel under the initial Yud י , when the Tetragram is to be read as Elohim, is the short

Hataph Segol ( ֱ ) which regularly stands under the Aleph א of Elohim אֱלֹהִים . This combination

in יהוה is ridiculous, as a Hataph Segol

is never found under a Yud י in a legitimate word.

It is under the Yud י in יהוה only to remind the reader to read, “Elohim,” and not, “Adonai.”

27. It becomes evident that the vowels assigned to יהוה in the Scriptures

are not the vowels which would allow one to speak it “according to its letters.”

Y’hovah יְהֹוָה and Y’hovih יְהֹוִה are

not, therefore, legitimate pronunciations. They are, in essence, linguistic

bastards. They represent the vowels of the nouns Adonai אֲדֹנָי and Elohim אֱלֹהִים ,

respectively, imposed upon the letters of a verb. Gesenius sums up the matter

nicely.

As it

is thus evident that the word יהוה

does not stand with its own vowels, but with those

of another word, the inquiry arises, what then are its true and genuine vowels?29

Y’hó

יְהֽוֹ , Yáhu יָֽהוּ and Y’hu יְהוּ

28. Since the Name cannot

be learned by looking within the Tetragram itself, we have to look elsewhere.

The first step in ascertaining its true pronunciation is, I believe, observing

how it is pronounced when it is part of men's proper names. It appears three

ways:

•

Y’hó יְהֽוֹ is how

the Name appears at the beginning and in the middle of a man's name. It has

two syllables. The first letter, Yud י , is pronounced as the “y” in “yes.” The Sh’va (

ְ ) under the

initial Yud י ( יְ ) indicates “the absence of a vowel.”30 It is such a slight sound that one hears little more

than the consonant with which it is associated. The first syllable is Y’- יְ- . The next letter,

Hei ה , is the first letter

of the second syllable. Pronounced as the “h” in “hoe,” it is often

treated as though it were a silent letter and disappears from both speech

and the printed page. The horizontal line ( ֽ ) under the Hei ה ( הֽ ) is the accent

mark. The accent is on the second syllable due to the nature of the Sh’va under the first.

The letter which follows the Hei ה is Vav ו , the third letter of the Tetragram. It is not a consonant

here, but a vowel, as there is a Holam ( ֹ ) above it. The Vav/Holam

combination ( וֹ ) is pronounced “oh”

like the “o” in “no.” The second syllable is -hó -הֽוֹ . The Sh’va under the Yud י , followed by the

often silent Hei ה , helps us understand why Y’hó יְהֽוֹ

is often found in a man’s name shortened to

Yó יֽוֹ .

•

Yáhu יָֽהוּ is how the Name appears at the end of a man's name.

The accent was assigned to the first syllable. The Kamatz ( ָ ) under the initial

Yud י ( יָ ) is pronounced

“ah” like the “a” in “father.” The first syllable is Yá יָֽ- . Instead of

the Vav/Holam combination ( וֹ

) after the Hei ה of the second syllable there is a Shuruk ( וּ ) which is pronounced

“oo” like the “u” in “flute.” The second syllable is -hu -הוּ . Yáhu is often found

shortened to Yáh יָֽה .•

Y’hu יְהוּ is how the Name sometimes appears at the end of one

particular name. The characteristics and pronunciation of the Yud י and the Sh’va of the first

syllable is the same as in Y’hó יְהֽוֹ

. The pronunciation of the Hei ה and the Shuruk (

וּ ) of the

second syllable is the same as in Yáhu יָֽהוּ

. Although the second syllable should take the

accent due to the nature of the Sh’va under the initial Yud י , the scribes saw fit to exclude it.Y’hó

יְהֽוֹ

29. When found at the beginning of someone's name, the

Name is pronounced Y’hó יְהֽוֹ

as in Y’hónatan יְהֽוֹנָתָן

(Jonathan) in

1 Samuel 14:6 & 8. Jonathan means, “

יהוה Has

Given.” When it appears in the middle of a man's name the pronunciation

is the same - Y’hó יְהֽוֹ

as in El’Y’hóeinai אֶלְיְהֽוֹעֵינַי (Elioenai). Elioenai means, “My Eyes Are Toward יהוה .” We find

this name in 1 Chronicles 26:3. As already mentioned, and as is common in

modern Hebrew, the Hei ה in Biblical Hebrew often

vanishes. So it is that we find Y’hó יְהֽוֹ

often shortened

to Yó יֽוֹ , Thus Y’hónatan יְהֽוֹנָתָן

becomes Yónatan יֽוֹנָתָן in 1 Samuel

13:2, 3 & 22 while El’Y’hóeinai אֶלְיְהֽוֹעֵינַי

becomes El’Yóeinai אֶלְיֽוֹעֵינַי

in 1 Chronicles 4:36.

Yáhu יָֽהוּ

30. When the Name appears at the end of a proper name it

is pointed Yáhu יָֽהוּ as in MíkhaYáhu מִֽיכָיָֽהוּ (Michaiah)

in 2 Chronicles 17:7, and EliYáhu אֵלִיָּֽהוּ (Elijah)

in I Kings 17. “Michaiah” means, “Who Is Like יהוה ?” while Elijah means, “ יהוה Is My Elohim.” This

pronunciation also gets shortened. Thus EliYáhu אֵלִיָּֽהוּ appears

in Malachi 3:23 as EliYáh אֵלִיָּֽה and MíkhaYáhu מִֽיכָיָֽהוּ becomes

MikhaYáh מִיכָיָֽה

in Nehemiah 12:35.

Y’hu יְהוּ

31. There are several examples of an exception to how the

Name looks at the end of proper names, but only in one name. In Judges 17

verses 1 & 4, I Kings 22:8 ff, 2 Chronicles 18:7 and Jeremiah 36:11 &

13, where we would expect to find Michaiah as MíkhaYáhu מִֽיכָיָֽהוּ

, we find instead MikháY’hu מִיכָֽיְהוּ

. To my knowledge, this is the only name in which

the Name is ever pointed like this.

Ecclesiastes

11:3 and Sham Y’hú שָׁם יְהֽוּ

32. We see three evidently related, but distinct pronunciations

of the Name in the Hebrew Scriptures. How do we explain this phenomenon? Perhaps

we should ask another question first: Do any of these pronunciations reflect

a legitimate verbal form? With this question, we reach a critical point in

our study. No longer can we simply observe the Biblical data. Now we must

evaluate it. The key to a proper analysis and the answer to our question is

found hidden away in the little read book of Kohelet (Ecclesiastes). There,

in the eleventh chapter, is a verse which apparently has been overlooked in

all the discussions about the Name. I came across it accidentally while reading

the Hebrew text one day many years ago. One phrase all but shouted at me from

the printed page.

קהלת

יא:ג אִם־יִמָּֽלְאוּ הֶֽעָבִים

גֶּשֶׁם עַל־הָאָרֶץ יָרִיקוּ וְאִם־יִפּוֹל

עֵץ בַּדָּרוֹם וְאִם בַּצָּפוֹן מְקוֹם שֶׁיִּפּוֹל

הָעֵץ שָׁם יְהֽוּא:

Ecclesiastes

11:3 If the clouds fill up with rain, they

empty upon the earth; and whether the tree falls to the south or to the north,

in the place where the tree falls, there

it shall be.

33. "There it shall be," translates sham y’hú שָׁם יְהֽוּא . Sham שָׁם means “there.” The Analytical Hebrew Lexicon, which

breaks up each word in the Hebrew text into its component parts, gives us

some very interesting information about the word y’hú יְהֽוּא . It is

a third person singular, masculine, Kal future (he will...) form of the verb

Hei Vav Hei ה.ו.ה. (to be)! ("Tree" is

a masculine word in Hebrew.) A note in brackets also informs us that y’hú יְהֽוּא is

apocopated (abbreviated as “ap.” or “apoc.”). “Apocopated” simply

describes “the loss of one or more sounds or letters at the end of a word...”31 Here is the entry:

יְהֽוּא

Kal fut. 3 per. sing. masc. [for יְהוּ ap. for

יֶהֱוֶה § 24. rem. 3] . . . . . . . הוה 32

34. According to the Analytical Lexicon the word y’hú יְהֽוּא

is a shortened verbal form of Yeheveh יֶהֱוֶה . It

reflects the meaning of the Name exactly and is identical in pronunciation

with how it is pronounced at the end of Michaiah's name sometimes. The note

in brackets also directs us to section 24 remark 3 at the front of the lexicon

where we read that y’hú יְהֽוּא is

a shortened “Syriac” form of Yih’veh יִהְוֶה

.

The

verbs הָיָה to be and חָיָה to live, which would properly have in the fut. apoc. יִהְי , and יִחְי , change

these forms into יְהִי and יְחִי

... A perfectly Syriac form is יְהוּא Ec. 11.3,

for יִהְוֶה , ap. יְהוּ (from הָוָה

to be).33

35. In the first quote from the Analytical Lexicon we are

told that y’hú יְהֽוּא is a shortened

form of Yeheveh יֶהֱוֶה , while in the second we read that it is a shortened

form of Yih’veh יִהְוֶה . The discrepancy arises from the fact that neither

of the longer forms is found in any Hebrew literature. The longer forms are

hypothetical reconstructions based on what we know of Hebrew verb patterns.

Since it is the shortened form which mirrors the pronunciation of the Name

in Michaiah’s name, it is the shortened forms of y’hi יְהִי and y’hu יְהוּ

which next require our attention.

Y’hi יְהִי

and Y’hu יְהוּ

36. So, we have in the words y’hí יְהִי

(root Hei Yud

Hei ה.י.ה. ) and y’hú יְהֽוּ

(root Hei Vav

Hei ה.ו.ה. ) shortened forms of the imperfect. Normally this shortened form

represents a nuance of meaning called the “jussive,”34 which expresses a “command or wish”35 and is recognized in Lamed-Hei ל"ה verbs36 by

the loss of the -ֶה ending of the usual imperfect.37 The third person masculine imperfect of Hei Yud Hei ה.י.ה.

is yih’yéh יִהְיֶה

. The shortened form is y’hí יְהִי

. Although we have no concrete witness as to the

long form of the third person masculine imperfect of Hei Vav Hei ה.ו.ה.

, we have the shortened form - y’hú יְהֽוּ . Working

backwards from there, based on the vowel pattern of yih’yéh יִהְיֶה , the grammarians

surmise that the regular imperfect is yih’véh

(yih’wéh)38 יִהְוֶה or

yehevéh

(yehewéh) יֶהֱוֶה as seen in the last two quotes above.

37. It seems odd, though, does it not, that the form of

the Name as it appears within so many personal names reflects not the usual

form of the imperfect, but the shortened form, the form that usually stands

for the jussive? So, what about Ecc. 11:3? Are we to understand it as, “Where

the tree falls, there let it be?” Is it a jussive? Actually, no, it is not. Gesenius,

in his Hebrew Grammer, says the jussive is often used for the regular imperfect.

He cites twenty specific instances where y’hí

יְהִי is used in place of the full form yih’yéh יִהְיֶה

Moreover,

in not a few cases, the jussive is used, without any collateral sense, for

the ordinary imperfect form, and this occurs not alone in forms which may

arise from a misunderstanding of the defective writing... but also in shortened

forms, such as יְהִי Gen 4917 (Sam. יִהְיֶה

), Dt 288, 1S 105, 2S 524, Ho 61, 114, Am 514, Mi 12, Zp 213, Zc 95, R 7216f. (after

other jussives), 10431, Jb 1812, 2023.26.28, 278, 3321, 3437, Ru 34.”39

38. It is evident that in the passages cited above by Gesenius,

where y’hi יְהִי is used for the ordinary imperfect, the final Hei ה of the full imperfect

form disappears. This is common for Lamed-Hei

ל"ה jussives. It is also evident that in Ecclesiastes 11:3

where y’hú יְהֽוּא is used for the ordinary imperfect, it does not lose

its final letter, but exchanges it for an Aleph א . This is most uncommon for

Lamed-Hei ל"ה jussives. Should we understand this phenomenon as a “perfectly

Syriac form” as Benjamin Davidson says? Or should we go with the opinion

of Gesenius that the true reading of Ecc. 11:3 is found in the few manuscripts

which read sham hu שָׁם הוּא

(there he is) instead of sham y’hú שָׁם יְהֽוּא (there he will be)?40 Or

is there yet another way of looking at it? Could it be that this shortened

form of the imperfect, which does not lose its final letter, is used for the

usual imperfect because the usual imperfect was never used for this particular

verb? Perhaps we should abandon our search for the “ordinary imperfect”

of Hei Vav Hei ה.ו.ה. and view y’hú יְהֽוּא as

the legitimate heir to the throne. Perhaps in this particular Lamed-Hei ל"ה

verb the jussive

and imperfect are not merely interchangeable as they appear to be in other

Lamed-Hei ל"ה verbs,41 but indistinguishable.

39. Stop and think for just a moment. The Name is a third

person singular, masculine, Kal future verbal form from the three letter root

Hei Vav Hei ה.ו.ה. (to be). At the end

of Michaiah’s name it is sometimes represented as Y’hu יְהוּ . It drops the final

Hei ה as it does within

every man’s name. It is a shortened form. Y’hú( א ) יְהֽוּא in Ecc.

11:3 is also a third person singular, masculine, Kal future verbal form, from

the root Hei Vav Hei ה.ו.ה. . It, too, is

a shortened form, but does not drop its final letter. Rather, it is changed

from a Hei ה to an Aleph א . What do we get when we change the “Syriac” style Aleph א back to its original

Hei ה ? We get Y’hú( ה

) יְהֽוּה . Is

there any difference in speech between y’hú(

א ) יְהֽוּא

with an Aleph א and Y’hú(

ה ) יְהֽוּה

with a Hei ה ? No. Neither the Hei ה nor the Aleph א affect the pronunciation.

They are both, for all intents and purposes, silent. And what do we get when

we return the lacking Hei ה to the Name as it sometimes appears at the end of Michaiah’s

name? We get Y’hu( ה ) יְהוּה

. And when we supply the accent it would have in

normal speech we have Y’hú(

ה ) יְהֽוּה

. Is there any difference in meaning between Y’hú( ה

) יְהֽוּה with

a Hei ה and y’hú( א

) יְהֽוּא with

an Aleph

א ? Grammatically,

no. Both express, “He will be.” But contextually there is a tremendous

difference, for y’hú( א ) יְהֽוּא

means generically, “he will be,” while Y’hú( ה

) יְהֽוּה is

the Name and quite specifically communicates, “He Will Be.” Perhaps that

is precisely the reason why Y’hú יְהֽוּ

in Ecc. 11:3 was written with an Aleph א and not a Hei ה . A change of the

final letter from a Hei ה to an Aleph א would be all that was necessary to distinguish the

ordinary, everyday, purely grammatical, "he will be," from the One whose name

means, "He Will Be," would it not?

Yahweh יַהְוֶה

40. By far, the most common pronunciation of the Name is

Yahweh יַהְוֶה . One

popular line of reasoning in support of this pronunciation has to do with

a statement made by Josephus. According to him, the Tetragram consisted of

“four vowels.” Speaking of the high priest’s garments, he says the following:

A mitre

also of fine linen encompassed his head, which was tied by a blue ribbon,

about which there was another golden crown, in which was engraven the sacred

name: it consists of four vowels.42

41. After reading this some have mistakenly concluded that

since Josephus calls the letters of the Tetragram, “Four vowels,” they

were pronounced as such: The Yud י is pronounced “ee,” the first Hei ה is pronounced “ah,”

the Vav

ו is pronounced

“oo,” and the final Hei ה is pronounced, “ay.” Put them all together and

you have, “ee-ah-oo-ay,” hence - Yahweh.43 The Scriptural evidence presented here, however, does not

lead us to this pronunciation. Nor does the structure and character of the

Hebrew language itself. In order to properly understand what Josephus meant

by, “Four vowels,” we must know something about that language, as he originally

wrote The Jewish War in Hebrew. He then translated it into Greek. Here it is

in his own words:

I have

proposed to myself, for the sake of such as live under the government of the

Romans, to translate those books into the Greek tongue, which I formerly composed

in the language of our country...44

42. It has already been shown that the common language

of Israel during the time of Josephus was Hebrew. The comment about the “Four

vowels,” then, was originally expressed in Hebrew. The only thing left of The Jewish War in that tongue is said

to be a “pseudepigraphic medieval Hebrew paraphrase...”45 It would not surprise me one bit to find the Hebrew

of that document to be written in a distinctive, Mishnaic Hebrew style. Perhaps

closer scrutiny would reveal it to be a bona-fide copy of the original and

not from medieval times at all. For now, though, we must be content with the

concept that the words, “Four vowels,” is an English translation of a

Greek translation of a Hebrew original which we do not have. The translation

is at best, second hand. It leaves us English-speakers with problems on several

fronts.

43. First, though it is true, as was pointed out earlier,

that Hei ה , Vav ו , and Yud י are known as “vowel-letters,”

it is not true they are always vowels. It would be accurate to say that in

a language of consonants, such as Hebrew, they can double as vowels. And when

they do, they are always preceded by a consonant. The consonants are said

to be “vowel carriers.” Vowels do not stand by themselves. It is, therefore,

quite impossible for the Yud י of יהוה to be a vowel.

It must be a consonant. The “Four vowels,” for this reason, cannot be

four vowels.

44. Secondly, there is no such thing as a Hebrew verb comprised

solely of vowels. It is the prescribed modification of consonants and vowels

which colors the verbal root with the various shades of meaning necessary

for successful communication. For this reason also, the “Four vowels”

cannot be four vowels.

45. Thirdly, it is precisely this modification of the Hebrew

verb which not only leads us away from the concept of the “Four vowels”

being pronounced as four vowels, but mitigates against the use of Yahweh as a valid verbal

form of any kind. The Hebrew verb is conjugated or "built" in seven different

ways. Each conjugation carries a slightly different nuance of meaning. In

simplified form they are as follows:

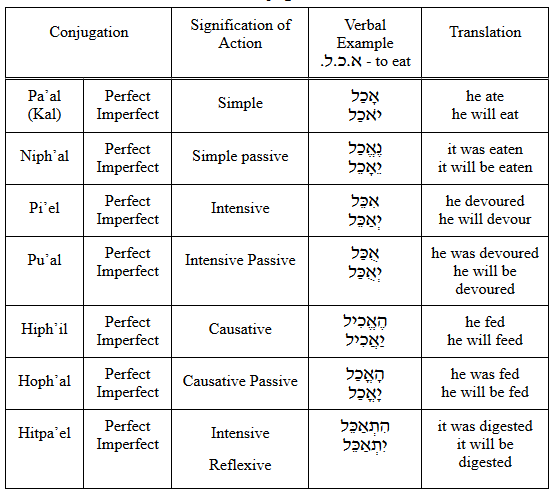

1. Pa’al

(Kal) - Simple

2. Niph’al

- Simple Passive

3. Pi’el

- Intensive

4. Pu’al

- Intensive Passive

5. Hiph’il

- Causative

6. Hoph’al

- Causative Passive

7. Hitpa’el

- Intensive Reflexive

46. Each conjugation has its own peculiar vowel patterns

for the perfect (past), imperfect (future), and present tenses. Each conjugation,

with its corresponding vowel patterns, modifies the simple, root meaning of

the verb, conveying a slightly different nuance of meaning.46 Not all verbs use all seven conjugations.

47. The vowel pattern of the word Yahweh יַהְוֶה identifies

it as a verb of the Hiph’il,47 the

so-called “causative” conjugation, from the root Hei Vav Hei ה.ו.ה. (to be) which

would literally mean, "He Will Cause To Be." That's a problem, though, because

the root Hei Vav Hei ה.ו.ה. , like its counterpart

Hei Yud Hei ה.י.ה. , has never developed

forms in the Hiph’il conjugation. In other words, Yahweh יַהְוֶה

, is a verb which does not exist in the Hebrew

language. It is wholly unintelligible.48 Even

if, for sake of argument, Yahweh יַהְוֶה

did represent a legitimate verbal form, the accent

would be on the last syllable (Yahwéh יַהְוֶֽה

) and his Name would mean, "He Causes To Be." However,

the "I AM THAT I AM" of Exodus 3 was communicated in the Kal conjugation,

not the Hiph’il. Therefore, the meaning of his Name is not to be associated

with the Hiph’il conjugation.

48. As a Hebrew speaker, Josephus knew all these things.

Unless he was guilty of promulgating disinformation, what he most likely meant

to convey by, “Four vowels,” and what his contemporaries most likely understood

when they heard it, was, “Four vowel-letters.” I believe the Hebrew original

of The Jewish War would bear this out. From our vantage point, however, there is

nothing in the words of Josephus which would lead us to understand that the

“Four vowels” were pronounced as such, let alone as “Yahweh.” The

structure and nature of the Hebrew language defy it.

Yáhu-Hei

יָֽהוּ "ה" ?

49. On the basis of its purely imaginary nature, Yahweh should be disqualified

from consideration as the actual pronunciation of the Name. As a Hiph’il

verbal form or a word made up of all vowels it is a phantom. Its legitimacy

ought to be seriously called into question. We know nothing, really, of its

origin. The case for this particular pronunciation rests somewhat precariously

on Greek and Latin manuscript evidence. The variants are many. The pronunciation

of יהוה is reportedly represented in Greek and Latin49 as:

|

Greek

|

Latin

| |||||

|

Iaw, Iaou,

Ieuw (Y’hó

Yáhu, or Y’hu)

|

IAHO

(Y’hó)

| |||||

|

Iabe, Iawoue,

Iawoueh, Iawouhi, Iawouea (Yahweh?)

|

Jabe

(Yahweh?)

| |||||

|

Iaouai,

Iabai (Yahwai?)

|

IAUE

(Yahweh?)

50. In reading some of these transliterations, it does

seem like the sound “Yahweh” is what the transliterators were after, doesn’t

it? This puzzled me for some time as “Yahweh” is nonsense in Hebrew. Then,

one day, I came across this pseudo-scholarly statement about the Name:

The

יהו

represents YAHU-, and the final ה

represents -EH or -WEH.50

51. Something in the way

that was written just didn’t sound right. And then it hit me: It’s not

the Hebrew which represents the transliteration, but the transliteration which

represents the Hebrew! What if we turned the sentence around to reflect reality?

“-EH represents the final ה

and YAHU- represents the יהו .” That rang a

bell. If Yahweh really is an ancient pronunciation, is it possible that it is

in essence a blended form of Yáhu-Hei יָֽהוּ "ה"

- the form Yáhu יָֽהוּ and the name of the final letter Hei ה spoken at the end?51 Could there have been more than one or two original

“pseudonyms” used during second temple times? In addition to Adonai אֲדֹנָי and

HaShem הַשֵּׁם

, could there have been, or was there also Yáhu-Hei יָֽהוּ

"ה" ? This might account for the occurrences

of a few Greek transliterations which seem to communicate a Yahweh-like sound to

our ears. That is, of course, speculation on my part, but apart from speculation

I have no explanation as to its origin.

Summary

52. Those of us who believe that the written Word is the

standard by which all things are measured need to act like it. The practice

of addressing the Almighty exclusively by the title, “LORD,” is a Rabbinical

dictum which is not in harmony with the Word. Sure, he is the Master, but

that is not his Name, the Name by which he wants to be mentioned. We should be using

his Name. In fact, if we were following Biblical protocol, we would be using

his Name ninety-eight percent more often than the pseudonyms, “Adonai,”

or, “LORD.” That’s right - ninety-eight percent! In the Hebrew text

יהוה is found alone over 6,600 times and joined with Adonai אֲדֹנָי (Lord)

another 285 times.52 Compare that with

the 140 times Adonai אֲדֹנָי

(Lord) is used by itself,53 and we can see how far we’ve sailed off course. Isn’t

it about time we threw the worthless compass overboard and started using the

one that points north?

53. We began our study by looking for a form of the verb

Hei Vav Hei ה.ו.ה. which would communicate, “He will be.” This is what

his Name means. We found such a form in Ecclesiastes 11:3. We found, moreover,

that the vowel points of this verb match precisely the form of the Name as

it appears in numerous instances at the end of the name, “Michaiah.”

54. Since y’hú יְהֽוּא

at Ecc. 11:3 is an authentic verbal form, is it

not simple deduction to consider the form Y’hu יְהוּ at the end of the

name, “Michaiah,” as the genuine article as well? Should these two not

be taken as corroborating witnesses? When we can take y’hú יְהֽוּא at

Ecc. 11:3, exchange the substitute Aleph א for the original Hei ה , and come up with the same thing as when we take Y’hu יְהוּ within

the name MikháY’hu מִיכָֽיְהוּ

(Michaiah), and restore the proper accent and

dropped Hei ה , do we not have everything we need to identify יְהֽוּה as

the authentic form of the Name? Let me diagram it.

55. This leads us to understand the pointing Y’hó יְהֽוֹ and Yáhu יָֽהוּ within

other men’s names as modifications. In both cases the unaccented syllables

are the authentic ones. Both unaccented syllables are found together in the

unaccented Y’hu יְהוּ at the end of MikháY’hu מִיכָֽיְהוּ

(Michaiah). The Name, therefore, is not a “full

form imperfect” like Yih’veh (Yih’weh) יִהְוֶה

or Yeheveh (Yeheweh) יֶהֱוֶה

. If it were,

what need would the scribes have had to change the pronunciation of the “shortened”

imperfect Y’hú יְהֽוּ to Y’hó יְהֽוֹ and Yáhu יָֽהוּ

in the majority of proper names? If his Name was

Yih’veh (Yih’weh) יִהְוֶה

or Yeheveh (Yeheweh) יֶהֱוֶה

the shortened form Y’hú יְהֽוּ

would have been all the change necessary to keep

it from being spoken in keeping with Rabbinical tradition. And yet it is readily

apparent that the “shortened” form has been altered. That speaks volumes

in and of itself.

56. But it does not tell us why the name “Michaiah”

is not pointed consistently. Why the ambivalence? Why is it written now as

MíkhaYáhu מִֽיכָיָֽהוּ

, and now as MikháY’hu מִיכָֽיְהוּ

? Could it be that the scribes who pointed the

text, in those places where it reflects the actual verbal form, wanted to

be sure that his Name indeed endured “forever,” to “all generations,”

at least in a few places? Could it be that the name Michaiah was chosen to

carry this honored distinction because his name means, “Who Is Like יְהֽוּה ?”

Regardless of exactly why, when all the witnesses have been questioned, there

it is, the Name above all names. It is available to seekers of every generation,

embedded in the name MikháY’hu מִיכָֽיְהוּ

and in the text of Ecc. 11:3.

57. I would like to know why this phenomenon has not been

entered into the equation. Why has this information not made it into any discussions

about his Name? Is it not applicable? Is it not pertinent? If not, why?

58. I have one further observation to make. In each instance

where the Name is represented as Y’hó יְהֽוֹ

, it is at the beginning of the man’s name. The authentic,

unaccented Y’- יְ- is the first syllable. In each instance where the Name is represented

as Yáhu

יָֽהוּ , it is at the end of the man's name. The authentic, unaccented

-hu -הוּ is the last

syllable. Perhaps it contains a riddle?

יְהֽוּה

is the beginning and the end, the first and the last.

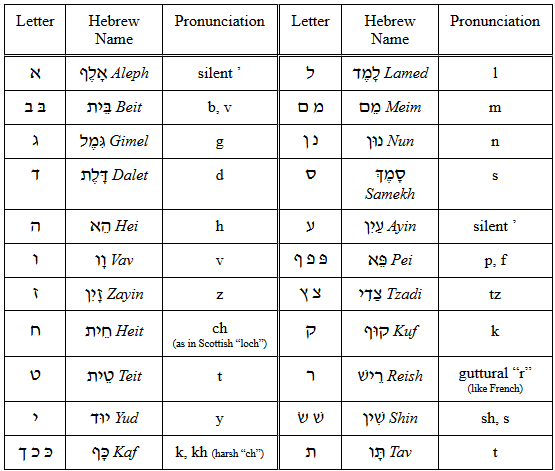

Table 1

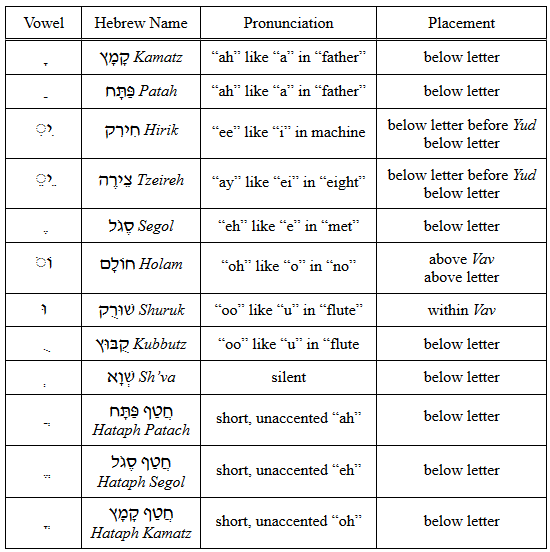

- The Hebrew Alephbet

Table 2

- The Hebrew Vowel System

Table 3

- The Seven Hebrew Conjugations54

1 Avraham

Even-Shoshan: Concordantziah Chadashah (Kiryat Seifer, 1983), pp. 440-448.

אַבְרָהָם אֶבֶן-שׁוֹשָׁן:

קוֹנקוֹרְדַנְצְיָה חֲדָשָׁה (קִרְיַת סֵפֶר, 3891), ד' 044-844.

2

In most English

Bibles “LORD” and “GOD” (all capital letters) are regularly employed

to represent the Tetragram where it appears in the Herbrew text.

3

The Hebrew reads:

אַף הַהוֹגֶה אֶת הַשֵּׁם

בְּאוֹתִיּוֹתָיו:

4

The Hebrew reads:

בַּמִּקְדָּשׁ אוֹמֵר אֶת

הַשֵּׁם כִּכְתָבוֹ: . See also Tamid 7:2.

5

Yoma 3:8, 4:2,

6:2; Sanhedrin 7:5, 8.

6 William Gesenius: Hebrew

and Chaldee Lexicon (Erdmans,1974), pp. 244-245.

7 The Hebrew is: מִצְוַת

אֲנָשִׁים מְלֻמָּדָֽה:

8 The Hebrew quotation from Isaiah is word for word,

including מִצְוַת אֲנָשִׁים

מְלֻמָּדָֽה - “the erudite

commandment of men.”

9 Two of the eight currently available, complete Shem

Tov Hebrew Matthew manuscripts read, “Keep doing everything he tells you,” meaning

Moses. The other six read, “Keep doing everything they tell you,” referring to

the Pharisees. The latter is in line with the Greek text from which come our

English translations. In my mind, whether Yeshua said, “He,” or “They,”

does not alter the meaning within the immediate context. The reference to

Mosaic authority is an appeal to submit to Moses. If we are to listen to the

Pharisees, it is only so far as their teaching accurately reflects Moses.

If not the actual words, the “he” reading of the two Shem Tov documents

is at least a clarification. Either way, we are to obey Moses and not pattern

our lives after the Pharisees. This conclusion should be inescapable in any

language.

It

is not within the scope of this article to either endorse or discredit the

Shem Tov Hebrew text of Matthew. I have quoted from it because it sheds much

light on the position the Master took against the oral traditions of his day.

For a crash course in the “reforms” and “precedent” based practices

of Pharisaic/Rabbinic Judaism and an introduction to Shem Tov’s Hebrew text

of Matthew, “the hebrew yeshua vs. the greek

jesus” is a good place to start and is

easy reading. Go to www.hebrewyeshua.com.

10 See also Jeremiah 23:27.

11 The word “Tanakh” is a Hebrew acronym which stands

for “Torah, Prophets and Writings.” Christians generally refer to this

collection of books as the “Old Testament.”

12 See Table 3 at the end of this article.

13 Gesenius: Lexicon, p. 221.

14 Gesenius: Lexicon, p. 337.

15 Gesenius: Lexicon, p. 219.

16 J. Weingreen: A Practical

Grammer For Classical Hebrew (Oxford, 1979),

p. 7.

17 Benjamin

Davidson: The Analytical Hebrew and Chaldee

Lexicon (Zondervan, 1972), p. 144.

18 Translations in brackets [ ] added for clarity.

19 John Parkhurst: A Greek

And English Lexicon To The New Testament (London,1809),

pp. 181-182.

20 The Mishnah is a compilation of what had been, until

then, the “Oral Law” of Judaism.

21 The Hebrew of the Mishnah is appropriately known as

“Mishnaic” Hebrew or “MH.”

22 Translation in brackets [ ] added for clarity.

23 M. H. Segal: A Grammar

of Mishnaic Hebrew (Oxford, 1983), p. 19.

24 Segal: Grammar, p. 15.

25 Segal: Grammar, p. 15, footnote 2.

26 William Gesenius: Hebrew

Grammar (Oxford, 1983), p. 37.

27 The Hebrew Alephbet and basic vowels, according to

the Sephardic pronunciation used in Israel today, are in Tables 1 and 2 at

the end of this article.

28 Avraham Even-Shoshan: HaMilon HeChadash (Kiryat Seifer,

1985), Vol. 2, p. 483.

אַבְרָהָם אֶבֶן-שׁוֹשָׁן:

הַמִּלּוֹן הֶחָדָשׁ (קִרְיַת סֵפֶר, 5891), כֶּרֶךְ שֵׁנִי,

ד. 384.

29

Gesenius: Lexicon, p. 337.

30 Menahem Mansoor: Biblical

Hebrew Step By Step (Baker Book House, 1992),

p. 33.

31 Merriam-Webster: New

Collegiate Dictionary (G. & C. Merriam

Co., 1997), p. 53.

32 Davidson: Lexicon, p. 300.

33 Davidson: Lexicon, p. 51.

34 Gesenius: Grammar, p. 129.

35 Gesenius: Grammar, p. 131.

36 Lamed-Hei ל"ה verbs have a Hei ה as the third letter of the root.

37 Gesenius: Grammar, p. 210.

38 In modern Israeli Hebrew, the waw ו of Biblical Hebrew

has a “v” sound.

39 Gesenius: Grammar, p. 323.

40 Gesenius: Grammar, p. 211.

41 Gesenius: Grammar, pp. 211-212.

42 Flavius Josephus: The

Jewish War 5:5:7 [5:235]( Translated by William

Whiston)

43 The Sacred Name (Qadesh La Yahweh Press, 2002), pp. 103-104.

44 Josephus: The Jewish

War 1:1 (Translated by William Whiston)

45 http://www.preteristarchive.com/JewishWars/

46 See Table 3 at the end of this article for an example.

47 See the paradigm for Lamed-Hei ל"ה verbs in section 24, p. 50 of the Analytical Lexicon.

48 Perhaps this is the real reason some think of the Name

as “heavenly.” If it isn’t a Hebrew word, it doesn’t have to mean

anything in Hebrew, does it?

49 The Sacred Name (Qadesh La Yahweh Press, 2002), pp. 108-111.

50 C. J. Kostner: Come

Out of Her My People (Institute For Scripture

Research, 1998), p. 1.

51 Try saying Yáhu-hei יָֽהוּ "ה"

quickly and repetitively sometime and see what

comes out of your mouth.

52 Even-Shoshan: Concordantziah

, pp. 17-18, 440-448.

אֶבֶן-שׁוֹשָׁן: קוֹנקוֹרְדַנְצְיָה, ד' 71-81, 044-844.

53 Even-Shoshan: Concordantziah

, pp. 17-18.

אֶבֶן-שׁוֹשָׁן: קוֹנקוֹרְדַנְצְיָה, ד' 71-81.

54

The translation

of the word א.כ.ל. - “to eat” was taken from Abraham S. Halkin’s “201

Hebrew Verbs,” page 12.

|