When and where did the "Lashawan" form of Hebrew originate? Answer

If the word ידעתי (yadatiy) is in the past tense, why do you translate it as "I know" instead of "I knew?" Answer

Why do we know how to pronounce "Satan," but not "YHWH?" Answer

Is the Hebrew word elo'ah the same word as the Arabic word allah? Answer

Which Hebrew words are used for God and which for false gods? Answer

If Judah (Yehudah) is spelled YHWDH (the name YHWH with a D) in Hebrew, if we remvoe the "D" does this reveal God's name as Yehu'ah? Answer

Why does your Mechanical Translation of Genesis 22:14 translate YHWH-Yireh as “YHWH appeared,” but other translations have “YHWH provided?” Answer

Did God create evil? Answer

Is God a he? Answer

Is the Hebrew word for God in the plural meaning more than one? Answer

Why do some people write the word "God" as "G-d" and "Lord" as "L-rd"? Answer

Why is Hebrew written from right to left? Answer

What does the phrase "Hand of God" mean? Answer

Why are some Hebrew words plural but translated in the singular? Answer

What does the phrase "heaven and earth" mean? Answer

Which should I learn first, Ancient/Biblical Hebrew or Modern Hebrew? Answer

What are the different forms of Hebrew verbs? Answer

Will I better understand the Bible by learning Hebrew? Answer

How can the same Hebrew word be translated as "lend" and "borrow" in Deuteronomy 28:12? Answer

How different is Ancient Hebrew from Modern Hebrew? Answer

What is the difference between a transliteration and a translation? Answer

Is the serpent of Genesis 3 a real serpent? Answer

What are the four compass points in Biblical Hebrew? Answer

Why are the plural words devarim ehhadim in Genesis 11:1 translated as a singular "one speech?" Answer

How can I know if a verb is in the perfect tense or imperfect tense? Answer

Why is the Hebrew word b'niym sometimes translated as "sons" and other times as "children?" Answer

What are the ס, the letter samehh, and פ, the letter pey (but sometimes ף, the final pey) that appear at the end of some sentences in Hebrew Bibles? Answer

Why is Hebrew written from right to left? Answer

When did Hebrew cease to be spoken? Answer

Did Moses Speak and write Hebrew or Aramaic? Answer

Do I need to know Hebrew to be able to read the Bible correctly? Answer

Why do you translate "El Shaddai" as "my breasts?" Answer

Where did the name "Jew" come from? Answer

Is there any evidence that the name Israel was originally spelled with a samehh rather than a shin? Answer

When and where did the "Lashawan" form of Hebrew originate?

I do not know when this started, but I suspect it was in the US a few decades ago. I do know that it was started by the Black Hebrew Israelites, a group of black people who believe that they are descended from the true Hebrews and the Jews of Europe and Israel are frauds. I believe that when they came to this conclusion, they believed that they needed to take control of the Hebrew language and make it their own and they did this by rejecting the vowel pointings (the vowel sounds) created by the Masorite (Hebrew was written without vowels originally) Jews. By doing so, they now have no way to pronounce the words, so they just added "a" between all the consonants. What they failed to recognize is that the Jews have been speaking Hebrew continuously (Not as a mother tongue, but they have certainly read and studied the Bible in Hebrew without interruption. So, while they created the vowel pointings, they were simply inserting the traditional vowel sounds that they have always pronounced since ancient times.

If the word ידעתי (yadatiy) is in the past tense, why do you translate it as "I know" instead of "I knew?"

Hebrew verbs have two tenses, perfect (completed action) and imperfect (incomplete action). The perfect tense is usually translated in the English past tense, but do not assume that it always in the past tense, as a completed action can also be in the present tense. In the case of the verb ידע (Y.D.Ah), which means “to know,” if we translated it in the past tense it would be “I knew,” which in English implies that the speaker no longer “knows” the individual. So instead, we would translate this verb as “I know.”

Why do we know how to pronounce "Satan," but not "YHWH?"

We assume the pronunciation "Satan" based on the traditional pronunciation of this word, but is this how it was pronounced 2,000 years ago? We really don't know for certain and there is no way to know how any word was pronounced in ancient times as there were no recording devices or pronunciation guides written. So, in reality, we know the ancient pronunciation of "satan" just as well as we know the pronunciation of "YHWH," it is just that as we consider the name YHWH to be of great importance so we are more cautious about how we pronounce it.

Is the Hebrew word elo'ah the same word as the Arabic word allah?

The Hebrew word אלוה (elo’ah, Strong’s #433) is used 57 times in the Hebrew Bible and is almost always translated as “God.” The parent root of this word is the word אל (el, Strong’s #410), which is also often translated as “God.” While this word is frequently used in the Bible as a descriptor of YHWH, it is also used for anything of “might.”

Derived from this parent root is the child root אלה (A.L.H, Strong’s #422) and means “to take an oath” or to “swear.” Our word אלוה (elo’ah, Strong’s #433) is derived from this child root and more literally means “The one of the oath.”

The “yoke,” which is used to bind two oxen together, is a perfect illustration of an oath. It was common to pair a younger inexperienced ox with an older more experienced one and the younger one would learn from the older one. When the Israelites entered into an “oath” relationship with YHWH, they were the younger inexperienced ox being yoked to the more mature one – YHWH.

The plural form of אלה (A.L.H, Strong’s #422) is אלהים (elohiym, Strong’s #430). Elohiym is a plural noun, identified by the iym suffix, that is often translated as “God,” “god” and “gods.” I should note that plural words in Hebrew do not always work the same way they do in English and a plural noun can be used in a singular sense.

The Arabic language is another Semitic language closely related to Hebrew and in Arabic the word Allah is indirectly related to the Hebrew word אלוה (elo’ah, Strong’s #433). The word Allah is actually two Arabic words; al meaning “the” and lah meaning “god.” It is the word lah that is a cognate (related word) of the Hebrew word אלוה (elo’ah, Strong’s #433).

Which Hebrew words are used for God and which for false gods?

In reality, the modern western concept, or what we think of as God or a god is completely foreign to the Hebrew text of the Bible. There are three Hebrew words used for God. The word el means one of power and authority and used for God in Genesis 1:1. The word elo'ah means one of power and authority which yokes himself to another and is used for God in Job 3:4. The word elohiym is the plural form of elo'ah and is used for God in Genesis 14:18. These same Hebrew words are also used for false gods. In Genesis 31:30 the word elohiym is used for Laban's household gods. In Habakukk 1:11 the word el'oah is used for the god of the goyim (nations). In Isaiah 45:20 the word el is used for a god of the goyim.

If Judah (Yehudah) is spelled YHWDH (the name YHWH with a D) in Hebrew, if we remvoe the "D" does this reveal God's name as Yehu'ah?

The pronunciation of some letters will change depending upon its position within the word. For instance, the letter beyt will be pronounced with a "b" if it is at the beginning of a syllable and as a "v" when it is at the end of a syllable. This is also true for the letter waw (vav in Modern Hebrew). When the vav is at the beginning of a syllable it will be pronounced with a w (v in Modern Hebrew), but when it us at the end of a syllable it will be pronounced as a vowel (o or u). In a name like יהודה (Yehudah), the waw is at the end of a syllable and therefore will be pronounced as a vowel (u). But in יהוה the waw is at the beginning of a syllable therefore it should be pronounced as a consonant (w).

Why does your Mechanical Translation of Genesis 22:14 translate YHWH-Yireh as “YHWH appeared,” but other translations have “YHWH provided?”

In this verse the phrase יהוה יראה appears twice. In the Masoretic Hebrew text dots and dashes called nikkudot (singular-nikkud) were added above and below the Hebrew letters to represent the vowel sounds. The first time this phrase appears in this verse it is written as יִרְאֶה (yir’eh) and means “YHWH sees,” but the second time it appears in this verse it is written as יֵרָאֶֽה (ye’ra’eh), which means “YHWH appears.” To explain the difference in meaning for the word יראה we need to understand the different verb forms. The verb יִרְאֶה (yir’eh) is the qal (simple) form and identifies the subject of the verb (which is YHWH) as third person, masculine, singular and the tense of the verb as imperfect and would be translated as “he sees” (“he” being YHWH). The verb יֵרָאֶֽה (ye’ra’eh) is the niphil (passive) form and also identifies the subject of the verb as third person, masculine, singular and the tense of the verb as imperfect and would be translated as “he was seen,” but means “he appeared.” However, remember that in the original text the vowel pointings did not exist, so we are relying on centuries of tradition for these verb forms being the qal and niphil forms. While the verb in question literally means “to see,” some translators have interpreted this to mean “to provide,” in the sense of “seeing” a need and filling it.

Did God create evil?

The Hebrew word for evil in Isaiah 45:7 is ra and literally means "bad" and is used consistently as the opposite of "good" (tov in Hebrew). While this sounds odd to most christians, God did create bad as well as good. Our western perspective of good and bad is not the same as the eastern/Hebrew perspective. We see everything as good or bad, we desire good and reject bad. The eastern mind sees both as positive or negative. If your whole life was filled with good, you would never know it as you can only know good if it is contrasted with bad. If you love ice cream and were able to eat ice cream your whole life never tasting anything else, you would not know ice cream tasted good because you have never tasted anything bad. All things have a negative and a positive without and one cannot exist without the other. We usually see light as good and darkness as bad. But if I filled your room with pure light you would be blind, and if I filled your room with pure darkness you would again be blind. In order to see, you must have a balance between light and darkness. In order to have a healthy life you must have a balance between good and bad.

Is God a he?

In English we use masculine (he), feminine (she) and neuter (it). But, in Hebrew all things are either masculine or feminine, there is no neuter. So, we may say "it is a tree" in Hebrew it would be hu ets (he is a tree). All things in Hebrew are either masculine or feminine. God is neither male nor female but he is both. This may sound contradictory but the Hebrew mind often seems contradictory from our perspective of western thought. In Genesis it states that God created both male and female in his image, I do not believe this is speaking in physical terms but in character. The male received half of God's character while the female received the other half, hence marriage is the bringing together of the two to make a whole. Since God has the character or quality of both male and female it is grammatically mandated that it is identified in the masculine form for the following reason. The Hebrew word for boy is yeled, the Hebrew word for boys is yelediym. The Hebrew word for girl is yal'dah and the Hebrew word for girls is yeledot. But if the group of children is boys and girls you always use the masculine yelediym. The masculine form always takes over if the group is of both masculine and feminine.

In Genesis 1:27 it states, and God filled the man with his shadow, with his shadow God filled him, male and female he filled them. In this verse it is clear God took a part of himself and placed it within both men and women, some of his attributes went to the man while others went into the woman.Is the Hebrew word for God in the plural meaning more than one?

The Hebrew word translated as "God" is elohiym. It is the plural form of elo'ah. While elohiym is plural. This does not mean that it is more than one. In Hebrew, a plural word may indicate quality as well as quantity. As an example, the Hebrew word ets is a tree. If there are two trees this would be written as etsiym meaning trees, qualitatively large. A large tree such as a Redwood could also be written etsiym, qualitatively large. As elohiym is plural, it can be translated as "gods" (quantity) or a very large and powerful "god" (quality). The creator of the heavens and the earth is far above any other god and is therefore elohiym, not just an eloah. The context the word is used will help to determine if the plural is qualitative or quantitative. If the plural noun is the subject of a verb, the verb will indicate if the subject is singular or more than one. For instance in Genesis 1:1 the verb bara (created) identifies the subject of the verb as masculine singular. The next word is elohiym (the subject of the verb) and is understood as a singular qualitatively large noun, God and not gods.

Why do some people write the word "God" as "G-d" and "Lord" as "L-rd"?

The practice of replacing a vowel in the words "God" and "Lord" with a "-" comes from the Jewish tradition of not writing out the names of God where there is a chance that the paper (or computer file) will be discarded (or deleted). This is derived from the command "Thou shall not take the name of the LORD your God in vain." It is their belief that if you write out the name and then discard it you are taking his name in vain. Any book, such as a Bible or Prayer Book that does spell out the name of God cannot be discarded but instead must be buried.

Why is Hebrew written from right to left?

In ancient times writings were done on stone with hammer and chisel. A right handed person will hold the chisel with the left hand and the hammer with the right hand. For this reason it needs to be written from right to left because of the angle of the equipment. When clay and parchments were used the direction remained the same but was also written from left to right. The direction the letters faced would indicate the direction it was to be read. By about 400 BCE the directions became standardized. The Greeks used the left to right while the Semitic people used the right to left.

What does the phrase "Hand of God" mean?

The Hebrew phrase is yamin elohiym. The word elohiym means "God" while the word yamin is "right hand". The focus of this word is on the idea of "the right hand" in contrast to just "the hand" (yad in Hebrew). The right hand is the stronger hand over the left hand. The "right hand of God" is an idiom for "the strength of God".

Why are some Hebrew words plural but translated in the singular?

Hebrew plurals can be either quantitative (more than one) or qualitative (great, large, prominent). For example the singular word elo'ah means God (or more literally mighty one). The plural form is elohiym. This plural form can be more than one god or one great god. In fact, in Genesis 1:1 it says "in the beginning elohiym (plural) created...” In Hebrew the verb matches the verb in number and gender and the Hebrew word behind "created" is bara literally meaning "he created" (singular masculine). Therefore, the context of the verse will often indicate whether the noun should be translated as a plural or a singular.

Some Hebrew words are always written in the plural form such as paniym (the plural form of paneh) which means "face" (probably through the idea of the prominent part of the body). The word shamayim (heaven) is another example of a word that is always written in the plural.

What does the phrase "heaven and earth" mean?

This is a Hebrew idiom meaning "all things". It should be remembered that the ancient Hebrew who wrote the Biblical text did not have a conception of the Milky Way Galaxy or the universe. Also they saw the heavens and stars as a canopy or tent covering over the earth. Genesis chapter one is not meant to be a scientific discussion on the origins of the solar system but rather a poetic story about God's involvement with his whole of creation.

It is quite possible that there are many Hebrew idioms in the Bible, the problem is that the definition of an idiom is a phrase that has no real meaning and is only understood from the culture the idiom is derived from. What this means is that their may be many other idioms but because we do not know them, we would never know them to be idioms. Therefore we often understand them as literal when they were never meant to be literal. Some idioms are known only because they have survived as idioms to this day. In Israel the expressions "good eye" and "bad eye" are still used to mean "generous" and "stingy". Both of these idioms can be found in both the Old and New Testaments (Proverbs 22:9, Proverbs 23:6, Matthew 6:22,23).

Which should I learn first, Ancient/Biblical Hebrew or Modern Hebrew?

First it is important that the term Hebrew, when applied to speech, can be divided into two parts;

- The script used to write the language which began thousands of years ago as pictographs similar to Egyptian Hieroglyphs and has evolved to the modern square script used today in Israel.

- The language and how thoughts and ideas are expressed in sentence form. Modern Hebrew is a modern abstract oriented language and is very different from Biblical Hebrew which is a concrete oriented language.

Once it is understood that Hebrew can mean the script and/or the language here is my recommendations for learning Hebrew.

- Learn the modern script as almost all published material on Biblical Hebrew uses this script. This way you will be able to use these materials.

- Learn the Biblical Hebrew meaning of words rather than Modern as your goal is to learn the meaning of the Biblical text. Only if you want to be able to speak to others in Hebrew, such as in Israel, than you need to learn Modern Hebrew.

What are the different forms of Hebrew verbs?

Hebrew verbs have seven different forms - qal (simple active), niphal (simple passive), hiphil (cuasative active), hophal (causative passive), hitpa'el (simple reflexive), piel (intensive active) and pual (intensive passive). Each form slightly changes the application of the verb as will be demonstrated with the verb "to cut" in the third person, masculine. The qal form is simply "he cut". The niphal form would be "he was cut". The hiphil form would be "he made cut". The hophal is "he was made cut". The piel is "he slashed". The pual is "he was slashed". A good Lexicon or dictionary such as Benjamin Davidson's Analytical Lexicon is very helpful in identifying these different forms in Hebrew verbs. A dictionary such as Strong's can be a little misleading. For example the verb ra'ah (Strong's number 7200) states that this word can mean "see" or "appear" but this is a little misleading. The word ra'ah means "to see," but when used in the niphal form it would be "was seen" which means "to appear". Thayer's dictionary is a little more helpful as it provides the different meanings based on the form of the verb.

Will I better understand the Bible by learning Hebrew?

Whenever a literary work is translated from one language to another a lot of the content will be, as the old saying goes, "lost in the translation." There is no argument that reading any work in its original language will provide a better understanding of that text. For instance, to really understand the works of Martin Luther it is best to read it in German and the works of Plato in Greek. This also applies to the Hebrew text of the Bible. As an example, the Hebrew word shalom is translated as peace but this does not convey the true meaning of the Hebrew which is to be whole or complete. Another aspect that is often overlooked is the cultural perspective of words. For instance the word rain means one thing to a farmer but something very different for a person on vacation. The Ancient Hebrews lived in a nomadic culture which views the world very differently from the way we do in our modern western culture.

It should also be understood that learning Hebrew will not always bring out the original intended meaning of a word or phrase. The problem is that we think from a western perspective and this is also true for those who speak Hebrew today. If we learn Hebrew with a modern western flavor, then we are simply learning modern Hebrew and not Biblical Hebrew. For instance the word tsadiyq is usually understood as "righteous" as identified in all modern lexicons and dictionaries of the Biblical Hebrew language. While we are comfortable using abstracts in our modern western minds, the Ancient Hebrews always understood things through the concrete. The original concrete meaning of the word tsadiyq is "to remain on the correct path."

A good analogy to show the difference between reading the Bible in Hebrew, or from an Hebraic perspective verses in English, or from a modern Western perspective, is to compare it to a Ravioli dinner. Would you agree that the dining experience would be very different if you were taken to a five star restaurant for a Ravioli dinner verses being served a bowl of canned Raviolis from a microwave? In both instances you are eating a Ravioli dinner and both of them will provide you with sustenance but the dinner served at the restaurant will more than likely have better flavor, atmosphere and additional side dishes. Reading the Bible in Hebrew, or with an Hebraic perspective, will have a greater degree of flavor, atmosphere and additional insights that would be missing in English.

To be honest, I believe that many people refuse to accept the fact that the Bible reads more accurately in Hebrew because they do not know Hebrew and would therefore be admitting that they do not know their Bible effectively. Are we students, myself included? Yes, none of us have all the answers or complete knowledge and truth but a student strives to learn the subject matter as well as possible with what resources are available.

In summary, learning Hebrew will enhance one's understanding of the Biblical text but the Hebrew must be learned through the ancient Hebraic mind and not the modern Hebrew mind. In my opinion it is more important to understand Hebraic concepts and thought and read an English translation than it is to know Hebrew fluently but use modern western perspectives for Hebrew words.

How can the same Hebrew word be translated as "lend" and "borrow" in Deuteronomy 28:12?

My standard comment about Strong's dictionary is that it is one of the best tools invented for people learning Hebrew but it is also the worst tool invented for people learning Hebrew. Strong's is great for people who do not know Hebrew to get a little exposure to it and learn a little more about the deeper meaning of Hebrew words but on the flip side Strong's has its limitations and if those limitations are not known it can create some problems, such as your question. It is true that the same Hebrew word is used for lending and borrowing but what Strong's cannot show you are the different tenses, prefixes, suffixes, moods and voices of each Hebrew verb. The Hebrew verb in question is lavah which literally means "to join" and is used in the context of borrowing in the sense of joining yourself to another. Where you see the word "borrow" the Hebrew has til'vah which means "you will join/borrow" (but the word preceding this is lo meaning "not" so it would then be translated as "you will not join/borrow." Where you see the word "lend" the Hebrew has vehilviyta which means "and you will cause to join/borrow." The main difference between the two is that the first one, til'vah is in the qal (or simple) form while the second is in the hiphil (or causative) form.

How different is Ancient Hebrew from Modern Hebrew?

This is a common question. Both Ancient Hebrew and Modern Hebrew are very similar in some respects. However, there are many differences as well.

- Modern Hebrew is written with the Aramaic square script, whereas the Hebrew Bible was originally written with the middle Hebrew script (Paleo-Hebrew).

- The Modern Hebrew language includes many words that could not have existed in Ancient times.

- The sounds for some of the letters have changed from ancient times.

- Ancient Hebrew verbs are written in two tenses, perfect and imperfect, which are related to the completion of the action of the verb. However, in Modern Hebrew, the verbs have three tenses, past, present and future, like other modern languages, which are related to the time of the action of the verb.

- While Modern Hebrew includes punctuations such as the period, comma, colon, etc, Ancient Hebrew did not have any punctuation.

- When the letter waw was prefixed to a verb in Ancient Hebrew, the tense of the verb is usually reversed (such as from perfect to imperfect) but this is not used in Modern Hebrew.

- In my opinion, the greatest difference between Modern and Ancient Hebrew is that the Modern Hebrew is an abstract language similar to other modern languages while the Ancient Hebrew language is a concrete language.

What is the difference between a transliteration and a translation?

A translation is taking a word from one language and changing it to a word from another language with the same, or in most cases a similar, meaning. As an example, the translation of the Hebrew word ארץ (erets) into English is "land." In reverse, the translation of the English word "heaven" into Hebrew is שמים (shamayim).

A transliteration is taking a word from one language and writing the sounds of that word using a different alphabet. As an example, the transliteration of the Hebrew word ארץ (erests) into Roman characters is "erets." In reverse, the transliteration of the English word "heaven" into Hebrew characters is הוון (heven).

In the Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, which was originally written in Hebrew, we find that Hebrew words are both translated and transliterated into Greek. In Hebrews 10:5 the Greek word Προσφορα (prosphora, meaning offering) is the translation of the Hebrew word קרבן (korban, meaning offering). In Mark 7:11 the Greek word κορβαν (korban) is the transliteration of the Hebrew word קרבן (korban, meaning offering).

Is the serpent of Genesis 3 a real serpent?

In Hebrew thought, the action or character of something is much more important than its actual appearance. In our culture, and forms of thought, it is either a serpent or it's not. But in Hebrew, the word nahhash (the word translated as serpent) is something that is serpent-like. This can be an actual serpent or something that acts like a serpent. Many times the authors of the Hebrew text do not make the distinction as we would. Such is the case here, we are not told if it is an actual serpent or someone or something that acts like a serpent. Our Greek thinking mind needs to know which it is, but the Hebrew thinking mind doesn't care. A good example of this is the Hebrew word ayil. This word literally means a "buck." But it is used in the Hebrew text for anything that is "buck-like," such as an oak tree, fence post, or a chief, all of which have the characteristics of being strong and authoritative.

There is one other piece to this puzzle that opens up another possibility for the identity of the serpent.

In that day the LORD with his hard and great and strong sword will punish Leviathan the fleeing serpent (nahhash), Leviathan the twisting serpent (nahhash), and he will slay the dragon (tanin) that is in the sea. (RSV: Isaiah 27:1)

In this verse, Leviathon is called a nahhash. So, it is possible that the serpent in Genesis 3 is Leviathon.

What are the four compass points in Biblical Hebrew?

The Ancient Hebrews related the four compass points to their geography in relation to the land of Israel. The word for East is קדם (qedem), which is the place of the rising sun. The word for South is נגב (negev), which is the desert region to the south. The word for West is ים (yam), which is a word meaning “sea” and refers to the Mediterranean Sea. Finally, the word for North is צפון (tsaphon), which comes from a Hebrew root literally meaning “hidden,” probably alluding to the idea that the northern regions were unknown to them.

Why are the plural words devarim ehhadim in Genesis 11:1 translated as a singular "one speech?"

The first thing that we have to recognize is the types of words in this phrase. The word דברים (devariym) is the plural form of דבר (davar) meaning a “word,” the plural form, דברים (devariym), therefore means “words.” The second word is אחדים (ehhadiym), the plural form of אחד (ehhad), which is frequently translated as “one.” But what we must also recognize is that חדים (ehhadiym) is an adjective, a word that modifies the word before it - דברים (devariym). In Hebrew, every adjective must match the number (singular or plural) of the noun it is modifying. So grammatically, if דברים (devariym) is plural, the word אחד (ehhad) must also be plural - אחדים (ehhadiym). The word אחד (ehhad) does not always mean “one,” but also “unified.” So now we can translate דברים אחדים () as “unified words,” which is a way of describing “a common language” or speech. Therefore, “one speech” is a fair translation of this Hebrew phrase.

How can I know if a verb is in the perfect tense or imperfect tense?

That is just a matter of learning the different forms of Hebrew verbs. But there is a general rule of thumb that will help make it a little easier. Specific letters are added to a verb to identify the number and gender of the subject of the verb. For instance, when the verb אמר (A.M.R/ to say) is conjugated as תאמר (tomer) it means that the subject is feminine singular and the tense of the verb is imperfect – "she will say." But when this verb is conjugated as אמרת (amarta) it means that the subject is feminine singular (same as before) and the tense of the verb is perfect – "she said." Generally speaking, when the number/gender letter (or letters) is added to the beginning of the verb it is in the imperfect tense, but when it is added to the end of the verb it is in the perfect tense. When this verb is conjugated as יאמר (yomer), it means that the subject is masculine singular and the tense of the verb is imperfect – "he will say." But when this verb is written in the masculine singular and perfect tense it is אמר (amar), there is no letter added to the end of the verb.

When I first started learning Hebrew I used an interlinear Bible with a dictionary and concordance (this was back in the day before computers were in every house) and looked up every instance of a given verb and wrote down the spelling and meaning. I found this to be a very useful tool for learning the different conjugations of verbs.

Why is the Hebrew word b'niym sometimes translated as "sons" and other times as "children?"

The Hebrew word for "son" is בן (ben) and "sons" is בנים (benim). The Hebrew word for "daughter" is בת (bat) and "daughters" is בנות (banot). However, if there is a group of mixed genders, in this case "sons" and "daughters," the Hebrew will use the masculine plural, in this case בנים (benim). When I am translating the Hebrew I will always translate it literally, so I will always translate בנים (benim) as "sons." Usually the context of the passage will dictate if this masculine plural is referring to only male children or male and female children. However, in the case of the tzitziyt there is no context to help with this interpretation. Traditional Judaism has decided that this is only referring to sons and not daughters, which is why Jewish women do not wear tzitziyt. Outside of Judaism, some believe that it is referring to only sons and others believe it is referring to sons and daughters. This is a decision each person or group must make.

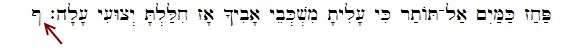

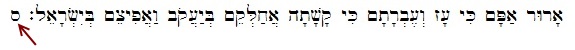

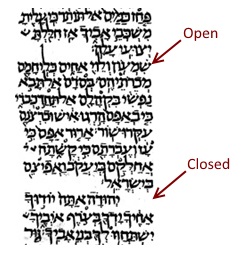

What are the ס, the letter samehh, and פ, the letter pey (but sometimes ף, the final pey) that appear at the end of some sentences in Hebrew Bibles?

Below is Genesis 49:4, as it appears in the BibleWorks Bible program, which includes the ף at the end of the sentence.

And below is Genesis 49:7, as it appears in the BibleWorks Bible program, which includes the ס at the end of the sentence.

The ף and ס are respectively called the petuhhah (open) and setumah (closed) and were not included in Biblical scrolls, codices and books, well not exactly, let me explain.

Below is Genesis 49:4-7 from the Leningrad Codex.

In this text are two different paragraph breaks. One is open, the petuhhah, and is always started at the beginning of a new line. The other is closed, the setumah, and never begins at the beginning of a line. In order to preserve the locations of the paragraphs, Bibles, especially electronic Bibles, will note their locations with the ס and ף, the final pey.

Why is Hebrew written from right to left?

Most ancient writing was done with a hammer and chisel in stone. The chisel was held in the left hand and the hammer in the right. From this position it is natural to write from right to left. When ink came into use, it was usually written from left to right to prevent the hand from smearing the ink. It was actually common to write Hebrew, as well as other languages, in either direction. The direction the letter faced informed the reader which direction to read it. At some unknown point in time, the actual direction became standardized. The Hebrews and other Semites continued with the original right to left, while the Greeks and other Europeans adopted the new left to right method.

When did Hebrew cease to be spoken?

Hebrew has been spoken in one form or another from the beginning. As we and others believe, Hebrew was the first language of Adam as well as Noah and his descendents. Noah had three sons, of which Shem continued the Hebrew language. When the nation of Israel entered the land of Israel after the exodus from Egypt (about 1500 BCE), they spoke Hebrew. When Israel was taken into Babylonian captivity (about 570 BCE) they continued to speak Hebrew (as we see in the book of Daniel). When Israel returned to the land of Israel (about 500 BCE) they continued to speak in Hebrew. Hebrew continued to be spoken during the 1st century CE (AD) as can be attested by many letters and documents found during the time. In 135 CE the Jewish revolt against Rome was defeated and Jews were expulsed from the land and dispersed around the world. At this point most Jews adopted the language of the country they resided in, but Hebrew continued to be spoken in the synagogues. In the late 1800's Eliezer Ben Yehuda began a resurrection of the Hebrew language as a common language for Jews which found its fulfillment in 1948 when Israel once again became a nation with Hebrew as its national language and is spoken there to this day.

Did Moses Speak and write Hebrew or Aramaic?

Abraham, the ancestor of Moses, did come from "Chaldee" where the Chaldeean language (or "Aramaic") was spoken. Both Aramaic and Hebrew are practically identical. They used the same script and the same root words. While Aramaic and Hebrew have some slight differences today, 3,500 years ago, the time of Abraham, the two languages were most likely identical.

Abraham is called a Hebrew because his ancestor's name was Eber (see the geneology of Abraham in the Bible). The Hebrew spelling for Eber and Hebrew are identitcal except that Hebrew ends with a yud basically meaning "descendent of Eber." Moses of course is descended from Abraham through Isaac-Jacob-Levi-Kohath-Amram. Moses would have spoken the same language as his family which is descended from the Hebrew Abraham.

The next question is what script Moses would have used to write. It is true that he did not use the square script used today or in the first century CE. At the time of Moses a more pictographic script (similar to Egyptian Hieroglyphics) was used. You can see some examples of this Early Semitic/Hebrew script on our site.

There is no record of Moses existing outside of the Bible but this does not mean that he was not a historical figure. It has been purported that many Biblical characters never really existed until they were discovered in the archeological record. Some examples of this are King David and the Temple (which some scholars had stated that neither had actually existed). This was until they were found in ancient writings recently discovered. King David is mentioned in the Tell Dan Inscription and the Temple is mentioned in the House of Yahweh inscription. Maybe an ancient inscription mentioning Moses will one day be found as well.

Do I need to know Hebrew to be able to read the Bible correctly?

Whenever a literary work is translated from one language to another a lot of the content will be, as the old saying goes, "lost in the translation." There is no argument that reading any work in its original language will provide a better understanding of that text. For instance, to really understand the works of Martin Luther it is best to read it in German and the works of Plato in Greek. This also applies to the Hebrew text of the Bible. As an example, the Hebrew word shalom is translated as peace but this does not convey the true meaning of the Hebrew which is to be whole or complete. Another aspect that is often overlooked is the cultural perspective of words. For instance the word rain means one thing to a farmer but something very different for a person on vacation. The Ancient Hebrews lived in a nomadic culture which views the world very differently from the way we do in our modern western culture.

It should also be understood that learning Hebrew will not always bring out the original intended meaning of a word or phrase. The problem is that we think from a western perspective and this is also true for those who speak Hebrew today. If we learn Hebrew with a modern western flavor, then we are simply learning modern Hebrew and not Biblical Hebrew. For instance the word tsadiyq is usually understood as "righteous" as identified in all modern lexicons and dictionaries of the Biblical Hebrew language. While we are comfortable using abstracts in our modern western minds, the Ancient Hebrews always understood things through the concrete. The original concrete meaning of the word tsadiyq is "to remain on the correct path."

A good analogy to show the difference between reading the Bible in Hebrew, or from an Hebraic perspective verses in English, or from a modern Western perspective, is to compare it to a Ravioli dinner. Would you agree that the dining experience would be very different if you were taken to a five star restaurant for a Ravioli dinner verses being served a bowl of canned Raviolis from a microwave? In both instances you are eating a Ravioli dinner and both of them will provide you with sustenance but the dinner served at the restaurant will more than likely have better flavor, atmosphere and additional side dishes. Reading the Bible in Hebrew, or with an Hebraic perspective, will have a greater degree of flavor, atmosphere and additional insights that would be missing in English.

To be honest, I believe that many people refuse to accept the fact that the Bible reads more accurately in Hebrew because they do not know Hebrew and would therefore be admitting that they do not know their Bible effectively. Are we students, myself included? Yes, none of us have all the answers or complete knowledge and truth but a student strives to learn the subject matter as well as possible with what resources are available.

In summary, learning Hebrew will enhance one's understanding of the Biblical text but the Hebrew must be learned through the ancient Hebraic mind and not the modern Hebrew mind. In my opinion it is more important to understand Hebraic concepts and thought and read an English translation than it is to know Hebrew fluently but use modern western perspectives for Hebrew words.

Why do you translate "El Shaddai" as "my breasts?"

The Hebrew language is a very concrete language and will frequently use words contrary to our western understanding. I believe that the translators didn't like the idea of calling God "my mighty breasts," so they used "God Almighty" instead. How I understand this phrase is that the function of the breasts is to provide nutrition to an infant, which is descriptive of God, the one who nourishes us. I'm sorry, I don't have any resource to quote from to support this, it is just my interpretation of this word based on my research into the language and culture of the Hebrews.

Where did the name "Jew" come from?

Yehudah (Latinized as Judah) was one of the 12 sons of Jacob and anyone descended from Yehudah was a Yehudiy.

The twelve sons of Yisra'el (Romanized as Israel) formed the twelve tribes of Yisra'el, which later became the nation of Yisra'el. Later, the nation of Yisra'el split into two nations, the tribes in the northern region were called the nation of Yisra'el and the tribes in the south came to be known as the nation of Yehudah (Romanized as Judah). The nation of Yehudah consisted of the tribes of Yehudah, Benyamin (Benjamin) and Levi. The nation of Yisra'el consisted of the other ten tribes of Yisra'el. Those living in the nation of Yisra'el were called Yisreliym (plural of Yisra'eli) and those living in the nation of Yehudah became known as Yehudiym (plural of Yehudi).

The nation of Yisra'el was taken into captivity and taken to Assyria and later the nation of Yehudah was taken into captivity and taken to Babylon. Eventually the people of Yehudah returned to the original land of Yisra'el, but because it was the nation of Yehudah that returned, the land was called Yehudah (Latinized as Iudea) and all of the people of Yehudah were called Yehudiym.

After the revolt of the Yehudiym in 135 AD the Yehudiym were expelled from the land of Yisra'el and were scattered abroad into many different nations, but retained their identity as Yehudiym, the ones who belong to the nation of Yehudah of the land of Yisra'el.

The Hebrew word Yehudah took on several transformations over the years as the word passed from Greek to Latin to German and to English. Initially, the Y became an I and the H was dropped and became Iouda. Then the I became a J, which originally had a Y sound and became Joud. Then the D was dropped and the J took on the J sound we know today and became Jew.

Is there any evidence that the name Israel was originally spelled with a samehh rather than a shin?

In the Masoretic text the name יִשְׂרָאֵל (yisra’el/Yisrael/Israel) is spelled with the letter שׂ (sin) representing the “s” sound, but the MT lexicon and the Ancient Hebrew Torah will use the spelling יסראל, with a ס (samech), also representing the “s” sound, in order to preserve the original spelling. It should also be noted that the Aramaic spelling of this name uses the samech (ס) and not a sin (שׂ), which confirms the original spelling with a samech. It is the opinion of the Ancient Hebrew Research Center that in the ancient past the letter ש (shin) always represented the “sh” sound and the ס (samech) always represented the “s” sound. At some time in the ancient past, before the Hebrew Bible was written, some words spelled with the samech shifted to a shin, but retained the “s” sound. When the Masorites developed the nikkudot (the system of dots and dashes that were added to the letters), they added a dot on the right side of the shin (שׁ) to represent the “sh” sound and a dot on the left side (שׂ)) to represent the “s” sound.