Part 1 (1-6-2017)

And Moses wrote down all the words of the LORD. - Exodus 24:4 (ESV)

Remarkable new evidence discovered by Dr. Douglas Petrovich may change how the world understands the origins of the alphabet and who first wrote the Bible. As to be expected, his controversial proposals have ignited contentious debate.

In this first of a three-part series, the background and importance of this issue will be explored before some of the specifics of the new finds and the pushback from other scholars is covered in part two.

A common teaching in schools for many decades has been that the Phoenicians developed the world's first alphabet around 1050 BC. This alphabet was believed to have then spread to the Hebrews and other cultures in the Canaan area over the next centuries, eventually being picked up by the Greeks and Romans and passed down to the modern alphabets of today. However, many may have missed the implications of this view for the traditional understanding that Moses wrote the first books of the Bible.

While writing had long been in use by the Egyptians and the people of Mesopotamia, they used complicated writing systems (hieroglyphics and cuneiform) that were limited because they employed nearly a thousand symbols with many more variants representing not just sounds, but also syllables and whole words. The messages they conferred were fairly simple, while the Bible uses complex forms of language. The genius of the first alphabet was to boil everything down to about two-dozen letters that originally represented the sounds of consonants only. From these few letters, every word of a language can be easily represented.

An example of cuneiform wedge shaped script that had hundreds of different symbols, some with 30 or more variants (from wikimedia commons)

For a work as sophisticated as the Bible, you need the flexibility of an alphabet. If the alphabet was not invented until around 1050 BC, then Moses could not have written the opening five books of the Bible four centuries earlier.

Now, new evidence that may change everything has been announced by Dr. Douglas Petrovich, an archaeologist, epigrapher and professor of ancient Egyptian studies at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Canada. Epigraphy is the study of inscriptions - making classifications and looking for the slightest distinctives between writing systems while defining their meanings and the cultural contexts in which they were written. After many years of careful study, Petrovich believes he has gathered sufficient evidence to establish the claim that not only was the alphabet in use centuries earlier than some believe, it was in the form of early Hebrew, something that almost no one has previously accepted.

Three Giants in the fields of Egyptology, linguistics and archaeology. Sir Flinders Petrie 1853-1942 (from wikimedia commons), Sir Alan Gardiner 1879-1963 (copyright Thinking Man films), and William Foxwell Albright 1891-1971 (from wikimedia commons)

The standard presentation of Phoenician being the first alphabet is curious, since scholars have long known of much older alphabetic inscriptions. In 1904-1905 Sir Flinders Petrie, the father of Egyptian archaeology, and his wife Hilda discovered several rudimentary alphabetic inscriptions in the copper and turquoise mines that were controlled by the ancient Egyptians on the Sinai Peninsula. Sir Alan Gardiner, the premier linguist of his day, deciphered some of the writings and proclaimed that they were a form of primitive alphabet and that they used a Semitic language. The script became known as "Proto-Sinaitic" and was dated to the late Middle Bronze Age in the 1600s or early 1500s BC. W. F. Albright, the American known as the father of biblical archaeology, popularized the idea that these were Semitic writings and many took up the idea that Israelite slaves were responsible for these inscriptions. Hebrew, as the world's oldest alphabet, was first claimed in the 1920's by German scholar Hubert Grimme. "Although Grimme identified some of the Egyptian inscriptions as Hebrew, he was unable to identify all of the alphabet correctly," explained Roni Segal, academic adviser for The Israel Institute of Biblical Studies, an online language academy specializing in Biblical Hebrew, who spoke to Breaking Israel News.

As modern skepticism about the biblical account of the Exodus period took hold late in the 20th century, scholars have generally retreated from the idea that the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions were the product of Israelite mine workers. Additionally, the discovery of many other alphabetic inscriptions in the Canaan area dated to the period from 1200-1050 BC prompted the need for a new category. These, and a few earlier fragments from that area that were all similar to the Proto-Sinaitic constructions, were labeled as "Proto-Canaanite."

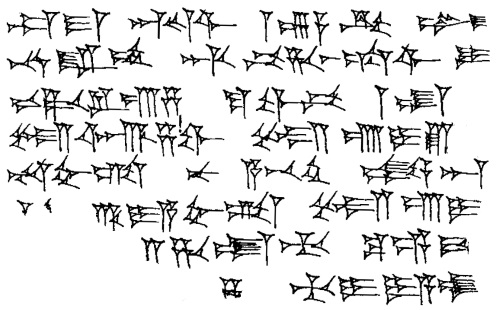

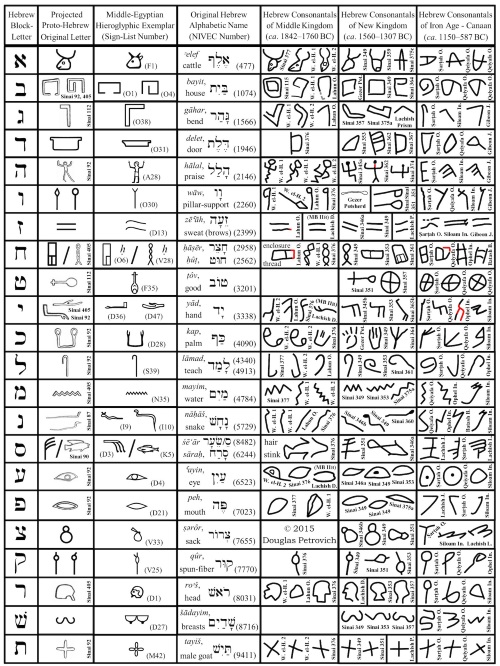

A comparison between the Hebrew block letters that came into use after the Babylonian captivity (that commenced about 586 BC), the proposed original alphabet of "Proto-Hebrew" and the Egyptian Hieroglyphs that may have been the basis for many of the letters. (from Douglas Petrovich)

The system for all these forms appeared to have been developed from Egyptian Hieroglyphics, which was used as a basis for creating 22 alphabetic letters representing consonantal sounds expressing the Semitic language of the writings. The first writings accepted by scholars as using "Hebrew" script are all from after 1000 BC and classified as using the "Paleo-Hebrew" alphabet.

The ironic thing is that these Paleo-Hebrew writings are often impossible to distinguish from the Phoenician ones and were just as much a natural development from the earliest Proto-Sinaitic and Proto-Canaanite examples. Yet most sources continue to communicate the standard paradigm. In their article on the Phoenician alphabet, Wikipedia states, "The Phoenician alphabet, called by convention the Proto-Canaanite alphabet for inscriptions older than around 1050 BC, is the oldest verified alphabet." This view is maintained despite the fact that the oldest examples don't come from Phoenicia and predate the existence of Phoenician culture. Might this practice be conveniently retained by those who don't want Moses to be considered as a possible author of the Torah?

Therefore, be very strong to keep and to do all that is written in the Book of the Law of Moses, turning aside from it neither to the right hand nor to the left. - Joshua 23:6 (ESV)

So did the Hebrew alphabet develop from Phoenician or was it the other way around? Could the earliest forms of the alphabet (Proto-Sinaitic and Proto-Canaanite) just as easily be considered as "Proto-Hebrew," and was it this early form of Hebrew that was the world's first true alphabet? This earliest form of Hebrew could have spread throughout the region and developed into what is now called Phoenician and Paleo-hebrew. The mainstream of scholarship has not gone in that direction, insisting that the most precise we can be with these alphabetic scripts is to say that they are Semitic, and Hebrew is only one variety of many Semitic languages from that time.

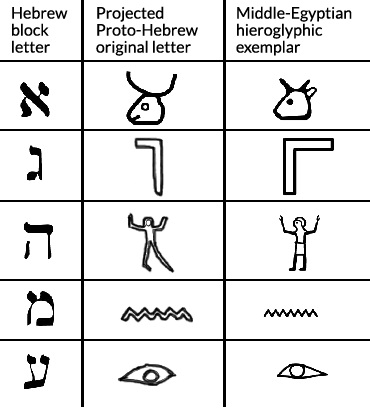

Things got more interesting when John and Deborah Darnell made a 1999 discovery in Middle Egypt of alphabetic inscriptions at a place called Wadi el-Hol. These appeared to be a hybrid between hieroglyphic symbols and alphabetic symbols that once again fit the scenario of hieroglyphs-to-Semitic-script scheme. The surprising thing was that they were dated to the 12th Dynasty, which in conventional terms equated to around 1850 BC.

A line drawing of some of the world's oldest alphabetic inscriptions from Wadi el-Hol in Egypt's Middle Kingdom (18th Dynasty) around the time of Joseph. - BRUCE ZUCKERMAN IN COLLABORATION WITH LYNN SWARTZ DODD Pots and Alphabets: Refractions of Reflections on Typological Method (MAARAV, A Journal for the Study of the Northwest Semitic Languages and Literatures, Vol. 10, p. 89) (from wikimedia commons)

These realities prompted more scholars to return to the possibility that these early scripts were connected to the Israelites' stay in Egypt. Egyptologist David Rohl theorized that the initial breakthrough may have come from Joseph during his time in power in Egypt, and that this system was later developed by Moses in time for him to begin writing what would become the first books of the Bible at Mount Sinai. Rohl wrote the following:

"...it took the multilingual skills of an educated Hebrew prince of Egypt to turn these simple first scratchings into a functional script, capable of transmitting complex ideas and a flowing narrative. The Ten Commandments and the Laws of Moses were written in Proto-Sinaitic. The prophet of Yahweh - master of both the Egyptian and Mesopotamian epic literature - was not only the founding father of Judaism, Christianity and, through the Koranic traditions, Islam, but also the progenitor of the Hebrew, Canaanite, Phoenician, Greek and therefore modern western alphabetic scripts." David Rohl (2002), The Lost Testament, Page 221.

However, these assertions have not shifted the position of most scholars. There just wasn't enough specific evidence to move these early alphabetic writings from the category of "Semitic" to that of "Hebrew." Enter Douglas Petrovich and his claims of new and multiple examples of just such specific evidence. Exactly what he has found and what some of the initial reaction has been will be the subject of Part 2 of this article in next week's Thinker Update.

Part 2 (1-12-2017)

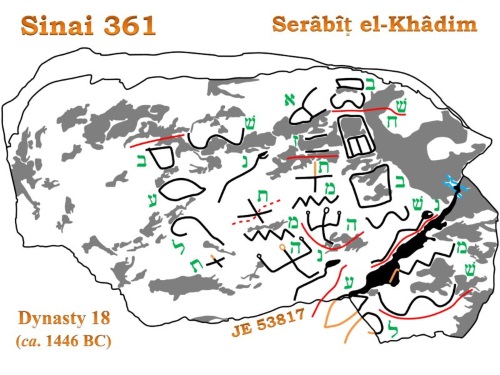

Sinai 361, part of a stone slab from Egypt, which Dr. Douglas Petrovich proposes contains the name Moses.

And Moses wrote down all the words of the LORD. - Exodus 24:4 (ESV)

In second of a three-part series, we will be looking at the controversial claims and startling new evidence from Dr. Douglas Petrovich that suggest the world's oldest alphabet was actually an early form of Hebrew.

I remember well the buzz around the halls and meeting places at the Evangelical Theological Society's meeting held in the fall of 2015 in Atlanta. Patterns of Evidence was there to promote their new film and book. The annual meeting featured hundreds of breakout sessions where leading Christian scholars from around the world presented their latest findings and proposals in their areas of specialization to several thousand attendees. With dozens of speakers to choose from during any given hour, deciding which session to attend was difficult. But the title of one presentation was the source of particular interest and excitement: "The World's Oldest Alphabet - Hebrew Texts of the 19th Century BC."

Groups I engaged with had already been talking about this presentation and as I negotiated the crowded hallways between presentations I overheard "I can't miss that one," from several hurried conversations. I knew I would need to get there early to secure a seat. It was the date in the title of the presentation that had captured the imaginations of so many. Hebrew texts that early in history were just so far beyond the normal scope of thinking (by about 1000 years) that they just had to see what was behind these fantastic claims.

Professor Douglas N. Petrovich.

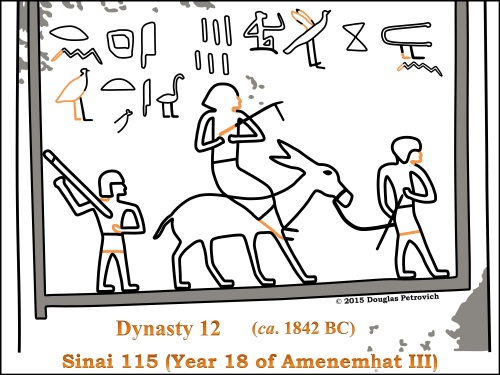

The presentation given to that overflowing room did not disappoint. Numerous examples of inscriptions were shown that not only pointed to Hebrew as the first alphabet, but also validated the biblical account of the Israelites in Egypt. Professor Petrovich had been studying the inscriptions on a series of 9-foot-tall stone slab markers called stele, which recorded the annual expeditions of a high official from Egypt down to the southwestern Sinai turquoise mines called Serabit el-Khadim. This is just west of the traditional Mount Sinai location. The official had recorded images of himself at the bottom of the stele where he was depicted on a donkey in the middle, with an Egyptian attendant walking behind him and a boy walking in front. Each year's inscription would show this boy growing taller. What caught his attention was that one stela did not use Egyptian hieroglyphics, but rather a rudimentary form of the alphabet in a Semitic language. If Petrovich's interpretation is correct it speaks of Joseph's son Manasseh and his son Shechem (Joshua 17:2).

The Manasseh inscription. (Credit: Douglas Petrovich)

The inscription included the date of Year 18 of Amenemhat III, the 12th Dynasty ruler around the time of Joseph in both the view of a Middle Bronze Age/Middle Kingdom Exodus around 1450 BC (represented in the film Patterns of Evidence: The Exodus by David Rohl and John Bimson) and in the view of a Late Bronze Age/New Kingdom Exodus at 1446 BC while retaining the conventional dating for Egypt (represented in the film Patterns of Evidence: The Exodus by Bryant Wood, Charles Aling and Clyde Billington and also held by Douglas Petrovich). This is because there are two main views for the length of the time the Israelites spent in Egypt - perhaps more on that debate in a future Thinker Update. Regardless, this date is more evidence that the Ramesses Exodus Theory held by the majority of scholars, may be causing them to miss evidence for the Exodus that actually exists centuries earlier than where they are looking.

If his interpretation is correct, it would also establish Hebrew as the world's first alphabet. According to Petrovich, the inscription says that this expedition included a group with significant connections to the early Israelites. He reads the inscription as, "Six Levantines, Hebrews of Bethel the beloved." The Levant is the area of Canaan and its surroundings. In the biblical account, Bethel was one of the headquarters of Jacob and his family before they moved to Egypt - it was their home town.

God said to Jacob, "Arise, go up to Bethel and dwell there. Make an altar there to the God who appeared to you when you fled from your brother Esau... And Jacob came to Luz (that is, Bethel), which is in the land of Canaan, he and all the people who were with him," - Genesis 35:1,6 (ESV)

Professor Petrovich said that the second of his forthcoming books will show clear proofs that the featured character can be none other than Manasseh the son of Joseph. This along with his other findings were again presented last November at the annual meeting of the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR), this time drawing the attention (and criticism) of a wider audience.

In Part 1 of the series it was shown that most academic outlets have long portrayed Phoenician as the world's first alphabet, which developed after the time of the Exodus and became the basis of all modern alphabets. This thinking has been propagated despite the fact that there has been clear evidence that the oldest examples of the alphabet don't come from Phoenicia and predate the existence of Phoenician culture. Leaders in the field would be careful not to ascribe the name of "Phoenician" to the first alphabet, but that message has not been getting out to the myriad of classroom and media outlets that continue to teach that.

This issue is critical for understanding the roots of the Bible, since the sophistication of the biblical narrative required an alphabet to be in place for it to be written. If the alphabet was first developed by Phoenicians in 1050 BC (or even around 1200 BC) that would mean Moses could not have been the author of writings that ended up becoming the first books of the Bible as tradition and the Bible itself claim. However, if the alphabet developed centuries earlier, in the very area where the Israelites are said to have been active in the years before and during the Exodus, then this would fit nicely with the claims of the Bible.

Many experts in the area of ancient languages have recognized that the earliest alphabetic scripts developed from Egyptian hieroglyphs and were in a Semitic language (the broad cultural group that the Israelites were a part of), but few have entertained the idea that this language may have been the more specific category of "Hebrew," the language of the Israelites.

As seen in an hour-long interview on Israel News Live, it started several years ago when Petrovich (an archaeologist and epigrapher at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Canada) was studying Egyptian inscriptions and "accidentally" ran into the inscription mentioning Manasseh. According to Petrovich this led to finding "one gold mine after another" in additional inscriptions. "Never in my wildest dreams did I think I would bump into three significant biblical figures on three different inscriptions that all date to the middle of the 15th century or so BC," said Petrovich.

It was only after defining every one of the 22 disputed letters of this early alphabetic script and which Hebrew letter each early sign corresponded to that Petrovich was able to interpret the Semitic inscriptions. This led him to eventually propose that the Israelites were the ones who transformed Egyptian hieroglyphics into the world's first alphabet. These texts mainly originated in the locations of Serabit el-Khadim and Wadi el-Hol in Egypt.

Another inscription, this one catalogued as Sinai 376 from the 13th Dynasty, Petrovich interprets as saying, "The house of the vineyard of Asenath and its innermost room were engraved, they have come to life." This sentence has three words (house, innermost room, engraved) in common with 1 Kings chapter 8 where it talks about King Solomon's construction of the Temple in Jerusalem. Asenath was the wife of Joseph and certainly one of the most famous women in Egypt at the time.

...And he gave him in marriage Asenath, the daughter of Potiphera priest of On... - Genesis 41:45 (ESV)

And to Joseph in the land of Egypt were born Manasseh and Ephraim, whom Asenath, the daughter of Potiphera the priest of On, bore to him. - Genesis 46:20 (ESV)

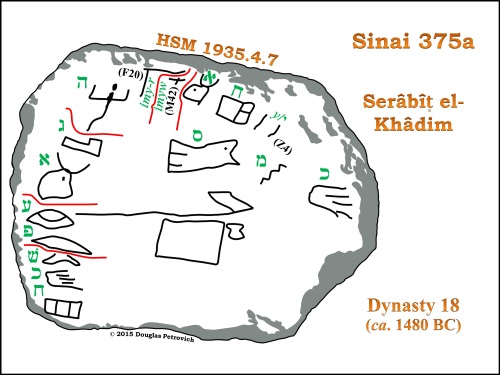

Two inscriptions from the time of the Exodus add fuel to the argument. In Sinai 375a (see below) Petrovich reads the name "Ahisamach" and his title, "overseer of minerals." Petrovich knows of no other instance of this name in any other Semitic language than Hebrew. In the Bible, Ahisamach was the father of Oholiab, who along with Bezalel was one of the chief craftsmen appointed for constructing the Tabernacle and its furnishings.

Sinai 375a with the etchings highlighted in black and the proposed Hebrew equivalents added in green containing the name "Ahisamach, overseer of minerals." (credit: Douglas Petrovich)

and with him was Oholiab the son of Ahisamach, of the tribe of Dan, an engraver and designer and embroiderer in blue and purple and scarlet yarns and fine twined linen. - Exodus 38:23 (ESV)

The second of the Exodus-era inscriptions is the most specific reference to the Exodus event. Naturally, it is also the most controversial of all. But that inscription, along with the debate that ensued, will have to wait for the final installment of our 3-part series on the world's oldest alphabet.

Part 3 (1-20-2017)

Sinai 361 (also photo below), with etchings highlighted in black and the proposed Hebrew equivalents added in green, which contain the name "Moses" in the lower right corner. (credit: Douglas Petrovich)

Then Pharaoh's servants said to him, "How long shall this man be a snare to us? Let the men go, that they may serve the LORD their God. Do you not yet understand that Egypt is ruined?" So Moses and Aaron were brought back to Pharaoh. And he said to them, "Go, serve the LORD your God... " - Exodus 10:7-8

In this third of a three-part series, we will look at perhaps the most profound and controversial interpretation proposed by Dr. Douglas Petrovich, and the debate that followed his announcements. As seen in Parts 1 and 2, Petrovich has proposed that there is now sufficient evidence to establish Hebrew as the world's oldest alphabet. If verified, this would push the first instance of Hebrew script nearly a thousand years earlier than previously thought, allowing the possibility that Moses actually was the author of the earliest writings in the Bible in the eyes of academia. This series of Egyptian inscriptions may also validate much of the history recorded in the Bible for the period of the Exodus.

Of the controversial texts that originated from Serabit el-Khadim, the turquoise mines controlled by the Egyptians just west of the traditional Mount Sinai, one in particular raises the temperature of this debate. Sinai 361 (hand drawing above and photo below) may contain the name "Moses" and actually refer to the year in which the plagues and devastation were visited on Egypt. The inscription is laid out in vertical columns from right to left with Moses (actually, the Hebrew "Moshe") being mentioned at the bottom of the first column on the right. Petrovich reads this inscription as follows:

"Our bound servitude had lingered, Moses then provoked astonishment, it is the year of astonishment, because of the lady."

The "astonishment" could pertain to the Judgment step seen in the film Patterns of Evidence: The Exodus when Egypt was devastated. The present tense used in the inscription could mean that the message was even written as the plagues were in the process of playing out.

But I will harden Pharaoh's heart, and though I multiply my signs and wonders in the land of Egypt, Pharaoh will not listen to you. Then I will lay my hand on Egypt and bring my hosts, my people the children of Israel, out of the land of Egypt by great acts of judgment. - Exodus 7:3-4 (ESV)

The references to bondage, a year of astonishment, and that this was provoked by "Moses," all remarkably fit the Exodus account of the plagues and exodus out of slavery in Egypt as described in the Bible. Petrovich believes "the Lady" spoken of refers to the Egyptian goddess Hathor, who was often depicted as a horned cow. The Bible records the Israelites' tendency to revere the gods of Egypt as seen in the golden calf incident at Mount Sinai. A reference to this rebellion and what may be the year of astonishment occurs in Psalm 78.

How often they rebelled against him in the wilderness and grieved him in the desert!

They tested God again and again and provoked the Holy One of Israel.

They did not remember his power or the day when he redeemed them from the foe,

When he performed his signs in Egypt and his marvels in the fields of Zoan.

He turned their rivers to blood, so that they could not drink of their streams.

He sent among them swarms of flies, which devoured them, and frogs, which destroyed them.

He gave their crops to the destroying locust and the fruit of their labor to the locust.

He destroyed their vines with hail and their sycamores with frost.

He gave over their cattle to the hail and their flocks to thunderbolts.

He let loose on them his burning anger, wrath, indignation, and distress, a company of destroying angels.

He made a path for his anger; he did not spare them from death, but gave their lives over to the plague.

He struck down every firstborn in Egypt, the first fruits of their strength in the tents of Ham.

Then he led out his people like sheep and guided them in the wilderness like a flock. - Psalm 78:40-52 (ESV)

Photo of Sinai 361, part of a stone slab from Egypt, which Dr. Douglas Petrovich proposes contains the name Moses.

This inscription (along with the Sinai 375a inscription naming Ahisamach) includes no date, but Professor Petrovich assigns a date in the 18th Dynasty around 1446 BC, based on pottery remains from that period found in the caves. David Rohl, who favors the Exodus occurring at the end of the 13th Dynasty, counters that pottery can only be used to date items found in the same layer as the pottery when dealing with stratified remains in the ground. So a separate inscription on a rock wall or Stela found above ground cannot be linked to any pottery finds, especially at sites in an area known to have a long history like this one.

Petrovich replied that the principle to which Rohl was referring does not apply to a carved mine, but only to sites where architecture experienced various phases of construction/reconstruction with new floor levels that cleared out old material regularly. In contrast, Petrovich noted that that these mining shafts were only used by a band of males who visited this remote site no more than once per year for seasonal/annual mining activity. There would not have been maids, cleaning services, or renovating within the mine shafts. If the mines that yielded New Kingdom inscriptions had been used in earlier periods, there would be visible evidence of it preserved in these shafts. Yet none exists.

While Professor Petrovich admits that the datable pottery evidence is no guarantee of the first use of the mines, he believes there is enough evidence along various lines to ensure that these particular mines were not used during the Middle Kingdom. And so the debate goes on. Petrovich believes his reconstruction of the development of the earliest Hebrew script also strongly supports his view that these later inscriptions are from the New Kingdom. Once again, whether late 13th Dynasty or early 18th Dynasty, these inscriptions appear to pre-date a Ramesses Exodus by centuries.

In an article in Breaking Israel News Petrovich points to other "Bible-esque" statements that he has deciphered. A statement reading, "Wine is more abundant than the daylight, than the baker, than a freeman," was found in an inscription from late in the 12th Dynasty.

Another inscription (this one from Sinai 375a, and nearer the time of the Exodus) reads, "The one having been elevated is weary to forget." While Professor Petrovich has not asserted this link, I find the wording uncannily similar to the account of Joseph being raised to second in command after being cast out by his brothers. This action caused him to be enslaved in Egypt and then thrown into prison for several years before being elevated.

Then Pharaoh said to Joseph, "Since God has shown you all this, there is none so discerning and wise as you are You shall be over my house, and all my people shall order themselves as you command. Only as regards the throne will I be greater than you." And Pharaoh said to Joseph, "See, I have set you over all the land of Egypt." - Genesis 41:39-41 (ESV)

Joseph called the name of the firstborn Manasseh. "For," he said, "God has made me forget all my hardship and all my father's house." - Genesis 41:51 (ESV) [Manasseh sounds like the Hebrew phrase for making to forget]

Petrovich explains that other Semitic languages do not result in sensible renderings for these inscriptions, which is why they have never been interpreted before. And few have thought the Israelites were this early, so Hebrew was not considered an option. This earliest version of Hebrew could be thought of as "Hebrew 1.0," and according to Petrovich it alone works at translating the Egyptian inscriptions. "There were many 'A-ha!' moments along the way," he stated, "because I was stumbling across Biblical figures never attested before in the epigraphical record, or seeing connections that I had not understood before."

Petrovich continued, "My discoveries are so controversial because if correct, they will rewrite the history books and undermine much of the assumptions and misconceptions about the ancient Hebrew people and the Bible that have become commonly accepted in the scholarly world and taught as factual in the world's leading universities."

As expected, criticism swiftly followed Petrovich's presentation at ASOR. The primary critique thus far has come from Dr. Christopher Rollston of George Washington University, one of the leading American scholars in the field of epigraphy and ancient inscriptions from the area of the Levant. On December 10, 2016, he wrote an article on his website titled: The Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions 2.0: Canaanite Language and Canaanite Script, Not Hebrew. In it he stated the following:

"As for the script of these inscriptions from Serabit el-Khadem and Wadi el-Hol, the best terms are "Early Alphabetic," or "Canaanite." Some prefer the term "Proto-Sinaitic Script." Any of these terms is acceptable. But it is absolutely and empirically wrong to suggest that the script of the inscriptions from Serabit el-Khadem and Wadi el-Hol is the Hebrew script, or the Phoenician script, or the Aramaic script, or the Moabite script, or the Ammonite script, or the Edomite script. The script of these inscriptions ... is not one of the distinctive national scripts (such as Phoenician or Hebrew or Aramaic, etc.), but rather it is the early ancestor of all of these scripts and we term that early ancestor: Early Alphabetic."

Professor Rollston is arguing that these inscriptions can't be called Hebrew because they are clearly "Early Alphabetic" or "Canaanite" (what many call Proto-Canaanite or Proto-Sinaitic), and Canaanite can't be said to be in any particular language, therefore it can't be Hebrew. But Petrovich is arguing against the very premise and the conventional thinking that the Early Alphabetic script can't be thought of as being in one particular national language. Obviously, some group of Semites who spoke some particular language developed it - and why not the Hebrews? The developers of the Early Alphabetic script had to be either the Hebrews or the Phoenicians or the Arameans or the Moabites or the Ammonites or the Edomites or the Midianites etc. One of them had to have been the first. And it just so happens that the Hebrews were in Egypt at just the time that this Semitic script developed from hieroglyphs into alphabetic symbols, and these earliest inscriptions just happen to feature the unique names of characters from the biblical story of the Israelites in Egypt and later during the Exodus.

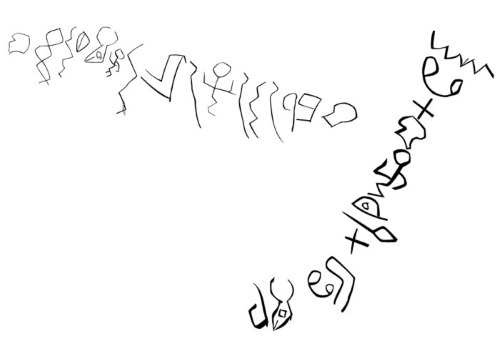

It is true that there is a script called "Hebrew" (or Paleo-Hebrew) that can be seen in inscriptions from around 1000 or 900 BC, and this "Hebrew" script is different than the earliest alphabetic script. But no one is disputing that point. The question is whether there is a precursor to that script - an earlier form of Hebrew (what Petrovich likes to call "Proto-consonantal Hebrew") - which was the world's first alphabet and has been called Early Alphabetic (or Proto-Canaanite) up until now. This script would then have developed into various branches used by the different groups in the region, including a gradual development into later forms of Hebrew like the one called Paleo-Hebrew today. The new book by Petrovich discusses this process extensively. He points to evidence showing that the Hebrew letters continuously evolved, becoming less pictographic over time, until eventually being converted into block letters.

The development of Proto-consonantal Hebrew as proposed by Douglas Petrovich

Rollston focuses the majority of his critique on Petrovich's interpretation of some words as "Hebrew" when they, in fact, appear in other Semitic languages and can have several possible meanings. But a large part of Petrovich's argument relies on the context of these inscriptions using uniquely biblical names in the correct time periods when those figures were active. Additionally his case rests on the claim that some of these inscriptions can only make sense when the Hebrew terms are supplied rather than the other options. To assess the strength of that argument, scholars will need to read the full proposal set out in Petrovich's new book, something no one has been able to do yet. Petrovich will lay out his findings in full in the first of his forthcoming volumes; The World's Oldest Alphabet available now for preorder through Carta out of Jerusalem.

In an exchange on Facebook, David Rohl said it was valid for Rallston to classify these early writings as Semitic. But Rohl pointed out that Rollston's reasons for not considering "Hebrew" as the type of Semitic involved, were dependant on his view that Israelites only existed in the centuries immediately preceding Ramesses II, and not as early as these inscriptions. If Rohl's (or Petrovich's) view was correct, the Israelites were around in the 12th Dynasty and Hebrew should be considered as a legitimate candidate for these earliest alphabetic inscriptions. Rollston responded, "Oh, David, you are so utterly mistaken about so much. It will serve no purpose for me to try to point such things out to you again...it would serve no useful purpose. So sorry. My analysis is based on actual inscriptions, diagnostic elements of language and script. Bless your heart. Be well and prosper. Sincerely, Chris"

The lack of willingness to engage in this important aspect of the debate caused Rohl to throw up his hands and say there is no way to force scholars to question their long-held traditions - academic inertia is hard to overcome. We look forward to continuing the debate in our upcoming Patterns of Evidence film series, hopefully with Douglas Petrovich and Christopher Rollston participating.

Professor Petrovich summed up, "Truth is un-killable, so if I am correct, my findings will outlast scholarly scrutiny. I have no doubt whatsoever that Hebrew is the world's oldest alphabet."